Tall Tales 22 Communicating

Some anonymous sources allege that speaking to yourself is the first sign of madness, don’t they? But having said that, what else can you do when you are totally alone and lonely? Under such circumstances, perhaps it’s the sound of your own voice resounding inside your head that keeps you sane. And then again, can you trust in the judgemental voices of those who say that you should not turn inside, nor create magical worlds full of imaginary friends, to find some comfort and avoid the cares of the every-day world? From time to time, furthermore, indulging in fantasy can help to solve perplexing problems and reveal hidden facts. As long as the voices within, which tend to resound usually in the deepest recesses of the soul, do not mislead you, nor tempt you to do evil, can we not agree that they are harmless at least, and exceptionally useful at best? That’s the conclusion of the contemporary shaman who believes that he has access to an alternative reality, through listening to the myriad voices inspired by particular substances and mental practices, where he can discover secrets and change the course of events.

Dear Fantastic Friend! [*] I realise you don’t reply straight away, if at all, most of the time, and then it’s in one of those weird trippy visions. But that’s no problem to me, I just like chatting, mate. I hope I can use such a word, but I feel like we’re friends by now. Anyway, I do miss hearing from you, and always wonder if you’ll reach out a mental tentacle, like. I’m sorry to start like this, I hate people who go on all the time, but I have to say it, whatever – I’m not expecting you to answer, mun! I know how busy you are what with the unofficial decorating and practising the conjuring tricks. I’m so glad that our mutual compadre, he-who-shall-not-be-named, passes my letters along to you, although these – what-d'ya-call'em – manly warriors – always work in dead mysterious ways, I gotta say! Par for the course with such famously renowned fellas, I guess.To be honest, I appreciate the chance to talk to someone, in the middle of all the carnage, uncertainty and fear, that’s all. By the way, excuse me Kimbric! I dunno how I can speak it at all, but it’s like there’s some little magical creature constantly chirpin’ down me ear’ole – feels like it’s been doin’ it all me life, somehow or other!

Why do they do things like this? Fighting over skin-colour, language, ethnicity? War’s Hell, and everyone’s in Heli-hrelí together in these hostilities. I’ve seen dead body-parts scattered all over the ground once or twice, y'know, when a bomb’s exploded near the supermarket. Men, women, children. It’s one thing to injure and kill adults, but the things they do with the kids! I’ve always had nightmares since when I was a child myself, no-one can explain why {Night Terrors}. It’s as if something hateful had happened to me that I can’t remember, like some infernal itch I can’t scratch. Believe you me, nothing’s got better by now, and now things’re worse in the real world too! Mam has to give me something special at night that helps me go to sleep. But even then, the familiar words that separate the sides from each other despite how simple they are, keep on flowing over me – ‘factory, tvornica, fabrika, usine, fábrica, fabbrica, gyár, fabrik, tehdas, ergostásio,’ for starters [**].

It makes my blood boil! I’ll never kill, except I want to kill the murderers. My Dad and the other soldiers want me to do abominable things to other kids but I always refuse. They won’t be able to make me behave so badly, and Oh, I get punished terribly. I’ve almost died several times, with more of the treacherous words filling my ears – ‘riža, rice, pirinač, riz, arroz, riso, reis, ris, riisi, óryza.’ And they took the mick of of me real bad when I peed myself that time. But I’m not going off anywhere, although I want to run far away from here. I’m a survivor! I’ve been thinking about stealing the old white van, mind you, and going for a spin in it with that Wýkinger, if he’s interested, but I’ve not decided yet.

My Dad’s a purveyor of highest-quality meat-products by profession, just like the old relations somewhere overseas in a town that was founded by the Wýkingren centuries ago, not too far from your own modest holiday cottage, I think {Future}. I’ve been reading everything about the place, especially after speaking with that Old Soldier, who’s a friend of Dad’s (and of someone else, too, nudge-nudge, wink-wink, I'll say no more!). He says he comes from there originally, and that it’s an incredible place to live in. He’s very experienced, professional too – my Dad, that is – everyone else seems to … respect … him – on our side, I mean. They – the dark forces of oppression on the other side – claim he’s nothing but a real blood-thirsty beast of a butcher by choice, though. They would do, s’pose, but I must admit he actually is a terrible, nasty, violent bully on occasions.

He goes out to fight, and kill people, while Mam helps them in the hospital. He goes out in the old white van with his gun and his knife while she gets a lift wearing her hat and her uniform, and her little upside-down watch. Dad likes his khaki military uniform too, especially the baseball cap with the picture of the flaming demon on it. I’m sorry the two of them look so tired all the time. Perhaps a bit of time off to relax in the house listening to ‘music, glazba, muzika, musique, música, musica, musik, musik, musiikki, mousikí’ would help them to feel better.

Some people think that the evenings are better than the days, that the darkness hides them, but no-one can avoid the sniper, that’s what Dad says. Hey, here’s how you know who’s who, even under cover of darkness. Well, after all the trial and tribulation with the Biblael Tower, by the language they use, that’s how, if they’ve got a tongue in their head anyway. Oh, ‘nogomet, football, fudbal, football, fútbol, calcio, fußball, fotboll, jalkapallo, podósfairo’ – I hate the beautiful game as a result!

And then there was that posh lad from the other side, who’d fallen off his motorbike on the front court of the garage on the bank of the river by the pines. We knew him, y’see, ‘cos he’s mad about my dear sister, everyone’s talking about him on the sly, although he was born into a family that belongs to the World-Wide Church, on the wrong side of the tracks, and they said, our men, that he should kill himself whilst saying his fake prayers. When he refused (no surprise there), all hell broke loose, and although he’s so brave, he was swearing like the blazes, they do know some great swear-words, those lads who go to services of the Other Church! But anyway, they were going to tar-and-feather him, those devilish cowards.

But it was me who put a stop to all that by sidling up and pouring petrol over the floor, and then setting fire to the old place and dragging the boy off. He’s OK to tell the truth, although he’s a member of the So-Called Church. As much as anything else, I’m sure that my sister wants a bit of company from a boy. She’s a beautiful girl, after all, and everyone needs someone at their side to set the world to rights, and the other stuff too, even in a war-zone.

He’s got blond hair, bit of Wýkingish blood in him, p’rhaps! Very intelligent, and reads comics all the time. But he’s got lots of problems as far as I know. I imagine he’s quite fond of the old confusticating clatchcreep, and the rest. And on top of that, he fancies my sister, something like that. I think he writes poems and sends them to her {Needed: More Minstrelsy!}. That’s why Dad hates him. I don’t care about that, he’s really brave, I’d like to be a friend of his. How much we’d scam people!

Mate, it was like a river of fire from the Old Book, or something. It was lucky, a small miracle, that I had a ciggie-lighter with me that time, ‘cos I’ve tryin’ to give up smokin’ for ages, honest! Oh, Lushfé who wept when he lost the battle, they were dancing like crickets in a frying pan on a hot-plate while they tried to put out the flames. Using water, the fools! And then there was the explosion. It almost blasted both of us off to the Nw Yrth. I had concussion from an injury to the head ‘cos of that, probably. I still can’t think right. Never mind about that, I was laughing at them for hours, when I came to my senses anyway!

I was hiding in the middle of the pine forest totally confused and covered in cuts-n-bruises with me clothes in rags like in some old zombie film. It felt like I was wearing sack-cloth and ashes like a mucky lost sheep from the middle ages beseeching the Priest-in-Charge in front of the door of a House of Penitence. But I’m not a member of the World-Wide Church, mun, never mind about my friends! Lurking, that is, until they caught me, more’s the pity. I’ve got quite a collection of really nice scars from head to toe as a result of the hiding I had. But at least I wasn’t in a real sack to get beaten like the other kids, the poor dabs! I can’t understand, I hate the old devil, my Dad, but he’s only doing what he thinks is right, in a way, to put me on the right path, that is the correct ‘cestička, put, drum, chemin, camino, sentiero, pfad, väg, polku, monopáti.’

And there’s a complex word for you – ‘dad, tata, òtac, baba, père, vader, papà, baštá, tad, isa, bampás.’ Well, not the noun itself, but the feelings. I can see how hard everything is. His eyes are as black as lumps of coal, and he’s always snorting stuff from that battered tin he takes with him all over. I wouldn’t be surprised if he took it to bed. Maybe it’s got his soul in it (sorry, his "four-eyes" – the "intangible indwelling of the inviolable instigant"). He’s fighting for freedom and truth, the brave old warrior. Wants to seize the land back for the future. Purify the ground. Get shot of the heathens. Save the people. Leave his mark on history. And he is brave, he’s seen awful things, he shouts about them in his sleep.

And then there’s Mam. For her part, she can’t stop coughing, and she keeps on gulping from that silver pocket-flask. I blame all the beetles there in the filthy hospital. You can hear them scuttling through all the air-shafts, whingeing chep-er, chep-er, chep-er, day and night. And talk about vile creatures, there’s Dad’s brother, or rather, ‘the Brother’ with his cowl and dirty robe, and the prayers, and the red eyes, and the hands with their nails like claws. I’ve see him looking at me, itching to do, well, I don’t want to think about what. But I’ll do something about him, you’ll see, I’ll really fix him good and proper yet!

I go out with Mam almost every day to the shop full of empty shelves to wait in a queue outside to get rations. Things like ‘mrkvy, sárgarépák, carrots, carottes, zanahorias, carote, möhren, morötter, porkkanat, karóta.' There’s not enough bread to be had anywhere – ‘kruh, chlěb, pain, pan, pane, brot, bröd, leipä, psomí, chleb’ – there are people attacking each other to get crumbs, and there’s only a bit of fresh water too. Of course the electric’s been gone for ages, so candles are awfully important. And then again, there’s the non-stop shelling with mortars.

It’s always raining here, even when it’s sunny, and everywhere there’s enormous holes full of blood and stagnant water, and mud. And now’n’then there’s body-parts all over the place. Really, I’ve seen ‘em, I’m not telling lies, mun! The Ubiquitous Vitality's Love, they say, but it looks like love’s dead, here, anyway! In the name of Wezir, the fabled shape-shifter, I’ve been reading about him, I need to transform myself somehow or other, so I can escape. I want to fly off from the battlefield like some old raven who’s had a gutful of pain and death. But I can’t leave my home, my family, my new friend, can I?

And, Oh, there’s my Mam, and my sis. I could never live without them, mun! (I don't like it too much at all, to say the least, when Dad makes me go travelling, hundreds and hundreds of miles sometimes, to help him do his all-important business, he says. It feels like we're always on the move, back and forth. Oooh, I get so sea-sick sometimes, and worry so much when we're away for weeks in strange places. And … there's other ... stuff … wonderful and ghastly magical things ... and the disgusting snuffling monster in me 'ead ... sayin' odd, hateful words to me ... tryin' to get me to fight back and hurt people awfully ... things like that, anyway, that I can’t talk to anyone about …) [***].

Look, bois, I gotta go – right sharpish! That's the old air-raid siren blastin' ... again! At least it'll make that demonic dragon go away for a bit. Well, till we meet next time – in our dreams (or our nightmares) ha ha! – Bye for now, matie!

* * * * * * * *

[*] This “letter”, allegedly written by Daud Pekar to Fred Llwynlesg (vidē īnfrā). is included in “Love, Loss, Coleoptera.” The original manuscript of this mysterious missive no longer exists (if it ever did – as is the case with so much of the “evidence” referred to here – to my undying shame and frustration!). This is, by his account at least, a faithful transcript made by F.Ll. who is, however, well, more than a little vague in his recollection regarding the “whens, hows and whyfors” of everything (in general) – and especially the nature of the “weird trippy visions” alluded to here. (The exact same observations pertain in various other places, too.) Putting this particular quibble aside for the nonce, I note in passing with a certain interest (combined with equal incomprehension), the similarity of the supposed young correspondent’s wording when referring to his father as “the brave old warrior,” and also to “that Old Soldier, who’s a friend of Dad’s [et cētera].” This is certainly suggestive of some obscure connection, but I cannot yet fathom what. — P.M.

[**] The words used here come from many of the languages spoken on the Northern Continent. I have been able to identify the following: Deysnika, Dutsh, ek-Kazlyano, Estlendi, Heladic, Hlownuní, Hwrgayn-ískw, Il'-Efranké, Italic, Kimbric, Laveyzh, Mad-gonyí, Madjungr, Neyrhlutsh, Nokshika, Peɾthe-heshe, Podlshizní, Pretanic, Ronmí, Rwzikzw, Sechrína, Shkíypya, Slowenshtína, Srpskor-vátskíy, Stlovchína, Sulondí, Tshechshina, Vhrlɡuhrskí, and Zveynsíka.

There’s no doubt that languages in every corner of the World change all the time. So, dialects that used to be mutually comprehensible at one time become separate languages as time goes on. Furthermore, it’s certain that people speaking different tongues have been claiming that these differences (as well as skin-colour, religious beliefs, political persuasions, and sophological teachings) justify atrocious actions against each other since when they invented language. (As my old mucker Fred Llwynlesg says elsewhere, “Why does everything have to change all the time? It’s not fair, not fair at all!”).

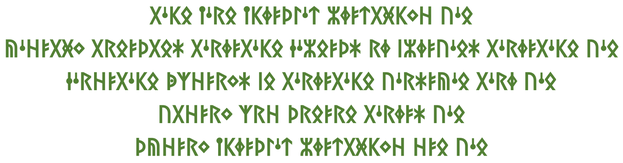

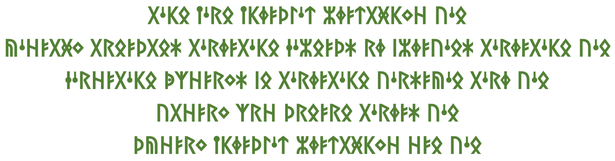

However, on a more positive note, I can report that the following. As a result of my researches into finding the “creātiōnis lingua” using Jack Procter’s notes, I’ve succeeded in recreating a possible version of the ancient "sigla" or glyphs that developed from Uthil Zuzas’s (or Uza-ma-Dauth’s) primal writing-system. The forms of the letters have stopped dancing and changing so restlessly and have begun to crystallize now, to a degree at least. Having said that, I have no idea yet about their sound; it’s as if there’s a legion of voices of all kinds blabbering, whispering, and singing in my head. Well, here’s the fruits of my labour so far for you, anyway:

I haven’t uncovered the Most Shocking Scarlet Sigil yet (thank goodness, many would say, in my fragile state of mind), and I already knew the forbidden Yellow Sign. However, I believe I have come close to guessing the form of the incredible Indigo Insignia. (The multi-coloured emblems appear unique to everyone considering them correctly, of course, if they can imagine them at all without losing it.) The act of inventing my own private language is certainly keeping the sparks of the Unquenchable Fire burning in me. So, I’ll stick with it, as I need substantial strength to complete the Great Work (and lots more than what I have at my disposal at the moment through the normal channels!). — P.M.

[***] When I read this part of Daud Pekar’s tale (which is so outlandishly creative and mature for the nib of such a young sprout that it almost beggars belief), I find myself getting lost in a welter of images. I have very sweet memories of the Heart of the Continent, dating back to the time when I, too, was knee-high to a grasshopper, so long ago and so far away in the unbelievable land of Hlîhra (Illuría, that is). In that mountainous landscape I was brought up under the green banner with its three-headed dragon, amongst the folk who were poor but proud, hale and hard-working, but rather dull in general, to be completely frank. In fact, the Haunted Homeland is the same size in terms of area as Kimbria together with Law·arya and Plantation Island in the Independent Commonwealth in the North of Meryk-land. Having said that, the populations of the two places – Kimbria and the Homeland – are the same, more or less, namely about three million people now. The shores of the River Zhêhdhw were home to my Mam before the most recent Great Commotion, and my childhood haunt, although my favourite place was the pine-forests around the Black Mountains of Ghrâzhghw in the west.

My Dad was a travelling salesman from the Independent Commonwealth, from a Kimbric-speaking family that had left Pretany (although a considerable number of people have used the name the Islands of the Disunited Kingdoms in the past and, more recently, the Land of the Repugnant Knaves) on the ill-fated ship called The Good Fortune. He used to drag himself over the whole wide World selling dental equipment to people who didn’t need it, for his sins, and was always fond of moaning that “The Immortal Power visits the transgressions of the offspring on the parents.” (For your information, there are lots of enterprising dental surgeons living on the blasted plains of the “Land of Plenty” today.) I moved to the land of my forebears for a little while after the fall of the Most Beloved Leader, but I didn’t feel too happy at all with the Paternalistic Dream, what with all the genuflecting before the flag and declaring allegiance to the Elected Autocrat of All Meryk-land, the shooting everything that moves with guns, the eating mountains of beef and chips, the enforced weekly self-abasement in the Civic Basilicas, and the training to be a dentist all hours of the day and night, and so on and so forth.

I fled for my life; I can’t say why exactly. And then I meandered hither and thither over the Worrisome World (and spent considerable time in the wild territories of the unexplored Southern Continent), striving to learn the rainbow-hued arts of bardism, mentalism, and phaneronics, and to reveal the secrets of enchantment. Well, there came across me at that time a strong but terrifying feeling (after by experiments with Saf-hilé’s Lamp, the Meh-tholé Stones, and the Pendulum of Sath-lafé) that a fateful change of circumstances would occur at the turn of the century and the millennium, and the start of the Age of Hustwr the Irrigator to boot. There was something calling me, forcing me, almost, to go to Kimbria to join in, to take part in the sweeping events that would develop in the Old-Land, so full of ancient charms and other-worldly energies. So, I came (with the help of my friends Frederick and Gertrude Llwynlesg) to visit my hero Daud, who was a teenage scribbler by then. He’d also fought in the Heart of the Continent before fleeing (or maybe returning) to Aberdydd to get treatment in the Clinic called The Pines for his terrible wounds. That was the beginning of my part in this story.

By the end of this piece by the young Pekar, it’s impossible for me not to bring to mind the Ragged Raconteurs, who’d crawl from town to town earning their crust by performing the ancient tales to be found in our national legends “le-Hnêthno al-Êmdlr” (like crazed members of some cyber-ascension group today, usually, the Impenetrable Mind protect us!). Ooh, the stories were (and still are) so alluring and gripping! My favourite one is “How Zrênthí Vêydjrow saved the Homeland and Destroyed the World.” I was particularly fond of a peripatetic troupe called “The Shambolic Storytellers” (under the leadership – if it can be called that – of Sâro se-Mŵnki), and I’m going to recount their version for you now. If you’re sitting comfortably, then I shall begin.

“Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw, or Atrocious Ivan with the Merciless Spirit, son to se-Vâhlw Hâymarks Trŵvlad, that is the Land-king Harry Oldtown, Rector of the Badlands, was an exceedingly strapping child, and exceptionally odious. The Father had killed his wife in cold blood as soon as the boy was born. And the Land-king was killed in turn by Vlâvw den-Dhêrah, the Warlike Foster-mother, who became an authoritarian guardian to the kid who despised her with every ounce of strength in him. The se-Dhômeh, the Baroness Exarch, was the name she chose for herself, at the start of her Reign of Terror, which would last for some sixteen years. Vlâvw established an iron dictatorship where she ruled like the most heinous Masters of Théybē in days gone by. She would terrify the folk, exploit them, use them as cannon-fodder in her interminable wars of aggression and conquest, and allow the survivors to starve and die of terrible diseases she cooked up herself. And although the populace hated her, they were too feeble and downtrodden to fight back. On top of that, she possessed a “hôrzhkadhve” or “horror-scope” containing living black fluid animated by inextinguishable green flame, a device which appears and functions uniquely according to the whims of its master and will safeguard him from harm by any mortal force.

“In order to pacify Dhvâno and govern him, den-Dhêrah would add enervating mildew to his meals every day, and if it were not for his other-worldly strength, he’d have gone nuts, hurt himself and others, and died. But instead of that, the natural psychedelic substances in the food only increased his lively imagination, helping him to escape from the hateful reality about him and survive, in some sense at least. Having said that, every hour of the day and night, whether waking or sleeping, was plagued by miraculous dreams mixed with spine-chilling nightmares about some Far-away Planet called se-Zêhlvado, Nova Terra, the New Eyrth. To be honest, he felt that he wasn’t living in the real world most of the time, and it was a complete mystery to him whether he was coming or going. This went on until the boy reached the age of maturity, namely fifteen years old in the Uncultivated Uplands.

“At that time, Dhvâno started to hear a voice calling to him. Although it was quiet and hard to understand to start with, the more keenly he listened to it, the clearer and more insistent it became. Under the influence of the Voice from Beyond, he would run off to an old shed on the outskirts of the walled fortress. There, a dear old black hen with golden eyes called Zrêndhw lived. And there also an enormous yellow lizard with eyes like a goat called Nîvdezh used to come to lurk in the shadows. Last of all, the ingenious boy had lured into a cage an albino wildcat with red eyes called Ghôhrw. Dhvâno would go every day to feed his feathery she-angel with fruit, vegetables and bread, borrowed from the larder; his chaos dragon with mealworm, ants and crickets he would get from an old blind fisherman living near the River Zhêhdhw; and his hairy devil with scraps of meat and fat from the cook whose husband the Tyranness had killed in a fit of bad temper. (The chef couldn’t stand Vlâvw to say the least, and she would help Dhvâno in other important ways later on too.) Whenever it was possible, he’d take berries, flowers, and nutmeg in order to worship the inseparable powers of heaven and hell – and the disorder that ruled them both – and pray for release from his servitude. The lost boy decided that Zrênthí Vêydjrow was the name of the inhuman entity that incorporated in this trinity of avatars.

“All these comings-and-goings went on for month after month, but den-Dhêrah’s eyes were everywhere, watching the child, and one day she sent a lackey to kill the hen and bring the carcase to her. Then, she arranged for it to be cooked and placed it in front of the Young Master and, grinning and gurning, chortling and slobbering all at the same time in the most alarming manner, she insisted that he eat. When he refused, without showing any emotion at all, she commanded that he be imprisoned in the ruined Disconsolate Rotunda completely alone for a fortnight. But so strong was his will, and so great his hatred, that he kept on praying to Zrênthí Vêydjrow, the Stalker amid the Stars, which had by now had become divinity and saviour to him. And here’s what he said to it, clamouring at the top of his lungs: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Lord of All, do just this one thing for me your son!’

“From somewhere unknown, the Immature Prince found some substantial vigour in both body and mind. When he came out of the Domicile of the Derelict Dome at last, he went immediately to collect plants of all kinds, including amaryllis belladonna, babies’ breath, bloodroot, daffodil, deadly nightshade, foxglove, hydrangea, iris, larkspur, lily-of-the-valley, marigold, morning glory, mountain laurel, oleander, tulip, tobacco leaves, wolfsbane, and yarrow. Then, he slipped off to visit the friendly cook, and she put five of these in den-Dhêrah’s dinner that night. But even then, she ate greedily, reproaching the boy – before falling on the floor twitching, foaming at the mouth, and gabbling incoherently. She’d put away so many drugs in her terrible life, however, that she came to her senses quickly enough. As soon as she could speak, she gave the command for Dhvâno to be locked in the deepest oubliette without food or water for three days and three nights until he almost expired. Despite all the tribulations, he kept on beseeching so insistently, over and over: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Lord of All, do just this one thing for me your son!’

“When the lad was released from the dark and freezing dungeon at last, he was in a terrible condition. He staggered off and was tended by a wise woman living in a mangled mill near the Boggy Pool. She gave him food and water, and told him that his aura was red, that is the colour of a warrior; that there was some exceptional power watching over him; and that he would be a great leader. About a week later, den-Dhêrah went out again, grabbed the yellow lizard, and throttled it with her own hands, before having the extensive skin turned into a pair of luxury slippers. When the Foster-mother made a show of herself in front of the lad, he said not a single word, but leapt at her and thrust a platinum knife into her leg as far as the bone. This time Dhvâno had added six other of his plants to the old witch’s food. But after hopping about the room like a pig full of unclean spirits screaming and shouting, she managed to pull the blade out of her limb before falling into a troubled sleep for twenty-four hours. When she awoke, she ordered the boy to be thrashed within an inch of his life. And indeed, the toadies of the Quartzite Fort almost beat him to death. Even then, the lad wouldn’t yield, and whispered under his breath in his anguish: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Lord of All, do just this one thing for me your son!’

“Dhvâno recovered remarkably quickly as if by some incomprehensible magic. Several days after that, den-Dhêrah went out again to investigate the blood-curdling loud squealing coming from the shed. There, she discovered the feral wildcat that was on the verge of starvation. After a furious fight, she managed to cut the creature’s throat, getting injured terribly by its poisonous claws at the same time. She went back to the Manse covered in blood with the cat’s bloody corpse and threw it on the table in front of the boy. This time, Dhvâno had added another seven of his plants to the worst she-devil’s food while she was about her abominable business. As she devoured her dinner, swearing and slobbering like a demented woman, so sore were the wounds that would never heal, Dhvâno threw highly flammable oil over her, and set her on fire with a candle. The commotion that ensued thereupon was enough to wake the dead. But, after all the writhing and cursing, den-Dhêrah put out the flames, although her flesh had melted like tallow.

“Vlâvw den-Dhêrah had murdered the three sacred creatures, Zrêndhw, Nîvdezh and Ghôhrw, performing a marvellous sacrifice without knowing it. Thrice had Dhvâno tried to kill her and thrice had she survived and come back to life. And now, like a legendary monster, she wanted terminal revenge on Dhvâno, the ungrateful, recalcitrant, murderous foster-son. Despite all her wounds, she commanded that Dhvâno be hung out of the Viridian Tower’s window by his arms for a day and a night, before being stoned to death. But even then, as he was being dragged off by the ankles, he chanted in his head: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Lord of All, do just this one thing for me your son!’

“And this is what came to pass then. As the boy dangled on the Viridian Tower, he entreated the hopeless, sickly crowd that gathered to stare open-mouthed at the pitiful sight, as follows: ‘I have discovered the truth. My whole life has been torture up to now. But, amidst the indignity, contempt and suffering, I’ve seen the future. You have only to sacrifice your children to Zrênthí Vêydjrow – the divinity of feathers, and scales, and fur, who is the master of living, dying and transformation, and adores blood, and sweat, and tears – to change the World. If you do this at midnight tonight, with the Sun having died and the Moon hiding her face, you shall be saved from the parasites who’ve been predating on you for centuries!’

“Of course, the people weren’t as stupid as to believe such nonsense, but they were in such a despicable state that they would have done almost anything to improve things to the slightest degree. So, most of them clambered onto to the roofs of their pigsty-like abodes dressed from head to toe in dark blue, the colour of mourning, carrying large lumps of chalk and baked clay, many of them fashioned, crudely or more artfully, into images, statuettes and effigies of their children. At midnight, with the Sun dead and the Moon hiding her face, they stabbed Dlôkda Lotké’s babies with daggers, and threw the children of Djŵkhta Swtakh to the ground, howling and groaning. Then they went to their beds to sleep like logs before awaking to the torture of life under the heel of the Warlike Foster-mother once more. And in the hot, humid air was heard the Vexatious Voice declaring unceasingly the old litany: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Lord of All, do just this one thing for me your son!’

“The next day, Vlâvw den-Dhêrah appeared, hiding the broken flesh disfigured by scars and scabs under a long grey gown, with a deep cowl about her head and a mask over her face, to punish and take revenge on the young rebel, and get rid of him once and for all. But Zrênthí Vêydjrow had heard the enthusiastic cries of the common-folk and accepted their fake sacrifices. Remembering and detesting its lineage, it materialized first in the form of a three-headed dragon, its three tails and three heads like a cat, its body like a lizard, and its wings like a hen, with feathers, and scales, and fur everywhere – and instantaneously began morphing into the most vulgar and tasteless harbingers. Den-Dhêrah was just about to plunge her toothed, black, and very sharp dagger of polished flint into the flesh of Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw, to humiliate him before the people before he was stoned to death (since it was believed that a man who died with a dirty body was unclean, unless this happened on the battlefield, and that he would be transported immediately to suffer pangs in the Bottomless Pit for ever). But the incubus descended on her, like a pillar of white flame and a column of black cloud, boiling with red blood and yellow bile. And then she absorbed the horrendous elements, and was filled up with them, and expanded, as her malformed body trembled more and more.

“Thrice Dhvâno had tried to kill den-Dhêrah and thrice she had survived and come back to life. Thrice had Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw been punished and humiliated, and thrice had he endured and grown in vigour. Three pure animals had the Baroness Exarch slain in an unwitting sacrifice, and all three of them had been resurrected (but not in the usual way, of course). And henceforth, the number three would possess magical qualities, as well as everything connected to it. No matter about that: now, peals of deranged giggling were to be heard, as ozone, sharp and tart, scorched the nostrils, and an indigo and ultraviolet flare blinded everyone.

“Within a short time, the body of the Warlike Foster-mother was trembling as if a hellish musician was revelling in destroying his instrument. And soon she was shaking as if an unseen monster was pawing at her devilishly roughly. In the end, every particle in the sickening ball of thrumming flesh decided to fly apart and escape to do evil wherever it could under its own devices. So did den-Dhêrah discorporate from within at last, but not before time, amongst clouds of arsine, batrachotoxin, botulin, chlorine trifluoride, cyanide, hydrogen sulfide, ricin, sarin, and strychnine. (There are some who gossip even today about how some kind of Shimmering Split in the Heavens opened up at that time, which the mortal remains of den-Dhêrah got sucked through.) And as this happened, se-Vârkha, the new World-king, declaimed his victory chant:

|

“‘Dhra zhla Zrênthí Vêydjrow kha; Ghŵdjo dlândai dhlêdhra shvâni le hvêkhai dhlêdhra kha. Shlŵdhra mbŵloi ha dhlêdhra khlîgha dhle kha, Kdŵlo blw nlâla dhlêi kha. Ngŵlo Zrênthí Vêydjrow ŵa kha!’ |

“‘Forth sallies Zrênthí Vêydjrow; Black his thoughts, and red his jaws. He brings death to his foes, Though they sue for peace. O Ferocious Zrênthí Vêydjrow!’ |

“Ferocious Zrênthí Vêydjrow (who-, or whatever that was), would not tolerate being mocked, however, nor prevented from receiving the appropriate sacrifice, either. The very same second that Vlâvw den-Dhêrah sublimed, every child in the Uncultivated Uplands vanished, and in its place stood (or lay, or sat) a statue of the kid, made of chalk or baked clay and wearing the blood-red gown of sacrifice. And each image was perfect, apart from the fact that it was completely faceless (and without a head at all, on occasions!). Where the children had gone, no-one would ever know, and there ensued considerable wailing and unfeigned breast-beating. But one thing was sure. Whenever one of the babies or young people amongst the plebs died from then on, the elder-men and elder-women would take the body away immediately, and cut off the head, and give it as a suitable and timely sacrifice to the vengeful and very powerful Zrênthí Vêydjrow in an unspeakable ceremony.

“After the discorporation of the Warlike Foster-mother’s substantial carcass, neither the matter, nor the energy, nor the vibrations in it in the first place (that is, the desires, the intentions, the personality, the will, and even the soul, according to some) had disappeared. They went on to have a terrible influence on the feelings, thoughts, and behaviour of every entity existing throughout the Unregenerate Orb from that time forward. Se-Vârkha Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw, the World-king Atrocious Ivan with the Merciless Spirit, Pontiff of the All-World, went forth also, to conquer, and desolate, and enslave in the name of Zrênthí Vêydjrow, the Stalker amongst the Stars. In his pride, his mercilessness, and his unbelief, he won the hatred of the So-called Church. But Dhvâno Dâjvowdh gave not one damn about that, and in truth. he savoured his notoriety, especially knowing that he now had a horror-scope or hôrzhkadhve to defend him from harm by ordinary beings under almost all usual circumstances at least. And although Zrênthí Vêydjrow guided Dhvâno’s mind and body, the Stalker between the Stars demanded complete obedience in exchange for its villainous patronage. So, Dhvâno would never love, nor ever be loved either, and Zrênthí Vêydjrow would appoint the place and time of his disappearance from our Heart-rending Homeland in due course, leaving nought but a humungous lump of coal behind.

“In the end, the bereaved folk brought forth new babies of course amidst the tumult, the fire, the blood, and the incessant harrowing screams. But to their great horror, every new-born child had violet skin (although that was bleached soon enough), and possessed characteristics of some animal or other, like the tail or paws of a cat; the comb, wattles or feathers of a hen; the eyes or hooves of a goat; the scales or tongue of a lizard. These would set them apart from their parents, who began to fear them, and distinguish them from the rest of the Dhrônlw, that is Humanity, who came to hate them. This also was the start of the furtive traffic in things of all kinds (including substances, artefacts, refugees, and ideas) between the persecuted proles of Hlîhra and those in Kimbria (as well as the swinish savages on the despicable Southern Continent).

“And the strife, the brutality, and the bloodshed in the Heart of the Northern Continent worsened and spread to poison every corner of the Sickly Sphere, under the green banner of the Thee-headed Dragon. As the Archimandrites of the Fake Church despaired at the spread of the Heresy of the Insoluble and Invincible Triunity, se-Vârkha Dhvâno laughed like a madman, and Zrênthí Vêydjrow remained utterly implacable in its desire for suffering and destruction. Thus, the war between the two factions persisted (for better or for worse), providing souls for the Miserable Maelstrom (or the Marvellous Mere according to the other side) for endless ages thenceforward. And it continues yet today, with the Evil Eyrth weeping bloody tears as it accelerates towards perdition, when it shall be drowned in rivers of black liquid before being consumed in imperishable green fire. All praise to Zrênthí Vêydjrow!”

So, there you have it in black and white, if not from the horse’s mouth itself – I’ve not heard the Story-tellers performing since the days of my adolescence. Ah, the fairest land is the childhood realm! The famous legend about how Hlîhra came to be font and epicentre of the bottomless hatred and the ceaseless conflict spreading over the crust of shw-Zêha Hrôzhdha, this Stupendous Spheroid. It explains why three is a mighty number; why the children born in the Heart of the Continent are so strong, and strange, and full of magical talents; and why there exists such murderous animus between the EGO’s Intercontinental Commissars and hoy-Aképhaloy or the Acephalites of Illuría. Then I start thinking of myself and my history, and although I know that I too am of this unique stock (splendid or squalid, according to one's point-of-view), I quake at the thought of failing to play – through ineptitude or unpreparedness – my proper part in helping to reshape our teary existence and bring the New Eyrth to be, here and now.

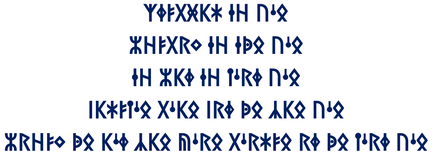

At the worst times, all I can do is follow my dear Gertrude’s advice. I lock myself in my bedroom, having placed images of the Homeland around me, light green and red candles, and play folk music on the mekafònotron, until my heart overflows with love and longing, loathing and lack. Then, I pick up a piece of soft charcoal in my sweaty paw, and write the following words in the most noble Illuric tongue and script on the old, plastered wall, whilst reciting them as earnestly as I can:

|

Bêdjri sw kha; Vŵdlo sw sma kha; Sw vre sw zhle kha. Hrîzha dhra hle ma pra kha; Vlŵo ma rhe pra ghla dhlîa le ma zhle kha. |

Bêdjri that's me; I always must be; I myself will be me. Don't you be frightened. Just wait and you'll see. |

Although this process does succeed in calming my jangling nerves to some extent every time, the wall is becoming extremely messy now. And I’m sorry to say I’m truly unsure as to whether I’ve ever whole-heartedly believed in the Fuchsia Spell, more’s the pity. But, well, there’s no knowing what’ll happen in the fullness of time anyway, I suppose. Wouldn’t you agree? Right, I’m going to leave it there for now. I’ll add more (probably) when I feel better again. — (Bêdjri Mngâkhri) P.M.

Hanesion Hynod 22 Cyfathrebu

Mae sawl ffynhonnell ddienw’n honni mai arwydd cyntaf gwallgofrwydd yw siarad â’ch hunan, onid ydynt? Ond wedi dweud hynny, pa beth arall y medrwch ei wneud pan fyddwch yn hollol ar eich pen eich hun ac unig? Dan y fath amgylchiadau, efallai mai sain eich llais eich hun yn atseinio y tu mewn i’ch pen sydd yn eich cadw yn eich iawn bwyll. Ac eto i gyd, a allwch ymddiried yn lleisiau beirniadol y rhai a ddywed na ddylech droi i mewn na chreu bydoedd hudol llawn ffrindiau dychmygol i gael hyd i ryw gysur ac i osgoi gofalon y byd bob dydd? O bryd i’w gilydd, ymhellach, mae llawenychu mewn ffantasi yn gallu helpu i ddatrys problemau dyrys ac i ddatgelu ffeithiau wedi’u celu. Cyn hired ag mai'r lleisiau oddi mewn, sydd yn tueddu i ddiasbedain fel arfer yng nghilfachau dyfnaf yr enaid, na fyddant yn eich camarwain, na’ch denu i wneud drwg, oni allwn ni gytuno eu bod yn ddiniwed o leiaf, ac yn eithriadol o ddefnyddiol ar y gorau? Dyna gasgliad y siaman cyfoes sydd yn credu bod ganddo fynediad i realiti amgen, drwy wrando ar y lleisiau fyrdd wedi’u hysbrydoli gan sylweddau neilltuol ac ymarferion meddyliol, lle y gall ddarganfod cyfrinachau a newid hynt digwyddiadau.

Annwyl Ffrind Ffantastig! [*] Dw i’n sylweddoli dwyt ti ddim yn ymateb yn syth, os o gwbl gan amla, ac wedyn ma’ mewn un o’r gweledigaethau hurtiol od ‘na. Ond ‘sdim ots ‘da fi am ‘ny, dim ond lico sgwrsio dw i, ‘achan. Gobeithio mod i’n gallu defnyddio’r fath air, ond dw i’n teimlo bod ni’n ffrindiau erbyn hyn. Ta be, dw i’n hiraethu am glywed oddi wrthyt ti bob amser, ac yn meddwl tybed fyddi di’n sgrifennu ‘nol. Mae’n flin ‘da fi ddechrau fel hyn, dw i’n casáu pobl sy’n cwyno bob amser, ond rhaid i fi weud ta p’un – sa i’n disgwyl i chi ateb, w! Dw i’n gwbod pa mor brysur wyt ti, rhwng yr addurno answyddogol ac ymarfer y triciau consurio. Dw i mor falch bod ein cyfaill cyffredin ni, yr hwn na ddylid ei enwi, yn pasio’n llythyrau i atoch chi, er bod y rheiny – bechingalw nhw? – y gwrol rhyfelwyr 'ma – wastad yn dipyn o deryn, on'd dyn nhw, raid i fi weud! Wel dyna rwbeth i ddisgwl gyda enwogion o fri fel 'na, 'sbo. A bod yn onest, dw i’n gwerthfawrogi’r cyfle i sgwrsio gyda rhwun, ynghanol yr holl laddedigaeth, yr ansicrwydd a’r ofn, dyna i gyd. Gyda llaw, esgusoda ‘Nghimbreg i! Sai’n deall sut dwi’n medru’i siarad o gwbl, ond mae fel ‘se rhw greadur bach hudol yn trydar yn ddi-baid yn ‘ynghlust i – mae wedi bod yn digwydd drwy gydol ‘yn oes rwbryd neu’i gilydd, am wn i!

Pam maen nhw’n neud pethau fel ‘yn? Brwydro dros liw croen, crefydd, iaith, ethnigrwydd? Uffernol yw rhyfel, ac mae pawb yn yr Uffern gyda’i gilydd yn y rhyfel ‘ma. Dw i ‘di gweld rhannau o gyrff marw wedi’u gwasgaru hyd y llawr, unwaith neu ddwy, t'mod, pan fydd bom wedi ffrwydro ar byws yr archfarchnad. Dynion, menywod, plant. Un peth yw anafu a lladd oedolion, ond y pethau maen nhw’n ‘neud gyda’r cryts! Dw i wastad wedi cael hunllefau er pan o’n i’n blentyn ‘yn hunan, ‘does neb yn gallu esbonio pam. Mae fel ‘sai rhywbeth cas iawn wedi digwydd i fi dw i ddim yn gallu'i gofio, fel rhyw ysfa uffernol sa i’n gallu ei chrafu. Credwch chi fi, dyw dim byd wedi gwella bellach, a nawr mae pethau’n waeth yn y byd go iawn hefyd! Mae rhaid i Mam roi rhywbeth sbesial i fi gyda’r nos sy’n helpu fi i fynd i gysgu. Ond hyd yn oed wedyn, mae’r geiriau cyfarwydd sy’n gwahanu’r ochrau oddi wrth ei gilydd er gwaetha’ pa mor syml ydyn nhw, yn dal i lifo drosta i – ‘ffatri, tvornica, fabrika, usine, fábrica, fabbrica, gyár, fabrik, tehdas, ergostásio,’ i ddechrau [**].

Mae’n neud i ‘ngwaed i ferwi! Fydda i ddim yn ymladd byth ond mod i eisiau lladd y llofruddion. Mae ‘Nhad i a’r sowldiwrs eraill eisiau i fi neud pethau arswydus i gryts eraill ond dw i’n gwrthod bob amser. Fyddan nhw ddim yn gallu ‘neud i fi fihafio mor ddrwg, ac, O, dw i’n cael ‘y nghosbi’n enbyd. Bu bron i fi farw sawl gwaith, gyda mwy o’r geiriau bradwrus yn llenwi ‘nghlustiau – ‘riža, reis, pirinač, riz, arroz, riso, rice, ris, riisi, óryza.’ Ac ro’n nhw’n ‘y ngwawdio i ar y naw pan ‘nes i bisio’n hunan y tro 'na. Ond sa i’n mynd bant i unman, er mod i eisiau rhedeg yn bell i ffwrdd oddi ‘ma. Goroeswr dw i! Dw i wedi bod yn meddwl am dwyn yr hen fan wen, cofiwch chi, a mynd am dro ynddi hi gyda’r Ficing ‘na ‘sai diddordeb ‘da fe, ond sa i ‘di penderfynu ‘to.

Cyflenwr cynhyrchion cig o’r ansawdd gorau yw ‘Nhad i wrth ei grefft, jyst fel yr hen berthnasau yn rhywle dros y môr mewn tre’ gaeth ei sefydlu gan y Ficingiaid ganrifoedd yn ôl, ddim yn rhy bell o dy gartre gwyliau diymhongar dy hunan, dw i’n credu. Dw i ‘di bod yn darllen popeth am y lle, yn enwedig ar ôl siarad gyda’r Hen Filwr ‘na sy’n ffrind i Dad (ac i rwun arall 'fyd: ond, hanner gair i gall, yma, mêt, weda i'm mwy!). Mae’n dweud fod e’n dod o ‘na’n wreiddiol, a fod e’n lle anhygoel o ddiddorol i fyw yno. Mae’n brofiadol iawn, proffesiynol hefyd – ‘Nhad, hynny yw –mae pawb arall yn ... ei barchu fe, maen ymddangos – ar ein hochr ni, dw i’n golygu. Nhw – grymoedd tywyll gormes ar yr ochr arall – sy'n honni taw dim ond bwystfil gwaetgar o fwtsier o'i wirfodd ydy’n wir, er ‘ny. Dyna beth a ‘nelen nhw, 'sbo, ond dwi'n goffo cyfadde taw bwli treisgar, brwnt, ofnadw yw e mewn gwirionedd, o bryd i'w gilydd.

Bydd e’n mynd i frwydro, a lladd pobl, wrth i Mam helpu nhw yn yr ysbyty. Mae’n mynd mas yn yr hen fan wen gyda’i gwn a’i gyllell tra mae hi’n cael lifft gan wisgo ei het, a’i wisg, a’i watsh fach ben i waered. Mae Dad yn lico’i lifrai milwrol caci hefyd, yn enwedig y cap pêl-fas ac arno lun o gythraul fflamllyd. Mae’n flin ‘da fi fod y ddau ohonyn nhw’n edrych mor flinedig drwy’r amser. Falle taw tipyn bach o saib i ymlacio yn y tŷ’n gwrando ar ‘gerddoriaeth, glazba, muzika, musique, música, musica, musik, musik, musiikki, mousikí’ fyddai’n helpu nhw i deimlo’n well.

Mae rhai pobl yn meddwl bod y nosweithiau’n well na’r dyddiau, bod y tywyllwch yn cuddio nhw, ond ‘does neb yn gallu osgoi’r saethwyr cudd, dyna beth mae Dad yn ddweud. Hei, dyma sut dych chi’n nabod pwy yw pwy, hyd yn oed o dan lenni’r nos. Wel, ar ôl yr holl drafferth a helynt gyda Tŵr Biblael, drwy’r iaith maen nhw’n defnyddio, dyna sut, os bydd tafod yn eu ceg ta be’. O, ‘nogomet, pêl-droed, fudbal, football, fútbol, calcio, fußball, fotboll, jalkapallo, podósfairo’ – dw i’n casáu’r gêm brydferth o ganlyniad!

A dyna oedd y llanc posh ‘na o’r ochr arall oedd wedi cwympo oddi ar ei fotor-beic ar gwrt blaen y garej ar lan yr afon ar bwys y pinwydd. Ro’n ni’n nabod e, ch’wel, achos fod e’n gwirioni ar ‘yn annwyl chwaer; mae pawb yn sôn amdano fe ar y slei, er iddo fe gael ei eni i deulu sy’n perthyn i’r Eglwys Fyd-Eang ym mhen tlotaf y dref, ac maen nhw’n dweud, ein dynion ni, fe ddylai fe ladd ei hunan wrth adrodd ei weddïau ffug. Pan wrthododd e (dim syndod yno), roedd helynt mawr, ac er fod e mor ddewr, roedd e’n rhegi fel tincer, gw’bod rhai llwon gwych mae’r llanciau ‘na sy’n mynd i wasanaethau’r Eglwys Arall! Ond ta be’, ro’n nhw’n mynd i ddodi tar a phlu arno fe, y cachgwn o gythreuliaid.

Ond fi roddodd ben ar hynny oll drwy sleifio lan ac arllwys petrol dros y llawr, ac wedyn tanio’r hen le a llusgo’r boi ymaith. Mae’n iawn a dweud y gwir, er fod e’n aelod o’r Eglwys Bondigrybwyll. Gymaint ag unrhyw beth arall, dw i’n siŵr bod y chwaer angen tipyn bach o gwmni gan lanc. Merch brydferth yw hi wedi’r cwbl, ac mae pawb angen rhywun ar eu hochr nhw i roi’r byd yn ei le, a ‘neud stwff arall hefyd, hyd yn oed mewn cylchfa ryfel.

Gwallt golau sy ‘da fe, tipyn bach o waed Ficingaidd ynddo fe, falle! Deallus iawn, ac yn darllen comics drwy’r amser. Ond mae llawer o broblemau ‘da fe hyd y gwn i. Dw i’n dychmygu fod e’n eitha’ hoff o’r hen fwg drwg, a’r gweddill. Ac ar ben ‘ny, mae e’n ffansïo’n chwaer i, rhywbeth fel ‘na. Dw i’n credu fod e’n ‘sgrifennu cerddi ac yn hala nhw iddi hi. Dyna pam mae Dad yn gasáu fe. ‘Sdim ots ‘da fi am ‘ny, mae’n reit ddewr, licwn i fod yn ffrind iddo fe. Cymaint o gastiau fydden ni’n chwarae ar bawb!

‘Achan, roedd fel afon o dân o’r Hen Lyfr neu rywbeth. Roedd yn lwcus, yn wyrth fach, roedd taniwr sigaréts ‘da fi bryd ‘ny achos mod i’n trio rhoi’r gorau i ‘smygu ers achau, wir i ti! O, Lushfé a wylai o golli’r frwydr, ro’n nhw’n dawnsio fel crics mewn padell ffrio ar blât poeth wrth drio diffodd y fflamiau. Gan ddefnyddio dŵr, y ffyliaid! Ac yna roedd y ffrwydrad. Bu bron iddo fe hyrddio ni'n dau bant i’r Nw Yrth. Ges i gyfergyd o ana’ i’r pen o achos hynny, siŵr o fod. Sa i’n gallu meddwl reit o hyd. Waeth befo am ‘ny, chwerthin am eu pennau nhw i gyd am oriau o’n i, pan ddes i at ‘y nghoed ta be'!

Ro’n i’n cuddio ynghanol y goedwig binwydd wedi 'nrysu’n llwyr ac yn doriadau a chleisiau i gyd gyda 'nillad yn rhacs fel mewn rhyw hen ffilm sombi. Fe deimlai fel ‘swn i’n gwisgo sachlen a lludw fel dafad golledig, fawlyd o’r canol oesoedd yn crefu ar yr Offeiriad mewn Gofal tu blaen i ddrws Tŷ Edifeirwch. Ond nage aelod o’r Eglwys Fyd-Eang ‘mo fi, w, hidiwch befo am ‘yn ffrindiau! Llechu, hynny yw, nes iddyn nhw ‘nhal i, gwaetha’r modd. Mae ‘da fi ryw gasgliad o greithiau neis iawn o’r corun i’r sawdl o ganlyniad i’r gurfa ges i. Ond o leia’ do’n i’m mewn sach go iawn i gael ‘y nghuro fel y cryts eraill, y pŵr dabs â nhw! Sa i’n gallu deall, dw i’n casáu’r hen ddiawl, ‘y Nhad, ond mae e’n neud dim ond beth mae’n feddwl yn dda, i’n rhoi i ar ben y ffordd, hynny yw, ar y ‘cestička, put, drum, chemin, camino, sentiero, pfad, väg, polku, monopáti’ cywir.

A dyna air cymhleth i chi, te – ‘tad, tata, òtac, baba, père, vader, papà, baštá, dad, isa, bampás.’ Wel, nage’r enw ei hunan ond y teimladau. Dw i’n medru gweld pa mor anodd yw popeth. Mae’i lygaid mor ddu â lympiau o lo, ac mae wastad yn ffroeni stwff o’r tun tolciog mae’n dod â fe o bant i dalar. Synnwn i’m ‘sai fe’n mynd â fe i’r gwely. Falle fod e’n cynnwys ei enaid (ma'n flin 'da fi, ei "bedair-a" – "arwisg anghyffwrdd yr achosydd anhalogadwy"). Brwydro dros ryddid a gwirionedd mae e, yr hen wrol ryfelwr. Eisiau cipio’r wlad yn ôl i’r dyfodol. Puro’r tir. Cael gwared ar y paganiaid. Achub y werin. Gadael ei farc ar hanes. Ac mae e yn ddewr, mae e ‘di gweld pethau ofnadw’, mae’n gweiddi amdanyn nhw yn ei gwsg.

Ac wedyn dyna Mam. O’i rhan hi, dyw hi ddim yn gallu peidio pesychu, ac mae hi’n dal i lowcio o’r fflasg boced o arian ‘na. Dw i’n bwrw’r bai ar yr holl chwilod yno yn y ‘sbyty brwnt. Ti’n gallu clywed nhw’n sgrialu drwy’r siafftiau awyr oll, gan gwyno chep-er, chep-er, chep-er ddydd a nos. A sôn am greaduriaid ffiaidd, dyna frawd Dad, neu yn hytrach ‘y Brawd’ gyda’r cwcwll a mantell front, a’r gweddïau, a’r llygaid coch, a’r dwylo ac arnyn nhw ewinedd fel crafangau. Dw i’n weld e’n edrych arna i, gan ysu i ‘neud, wel, sa i eisiau meddwl am beth. Ond fe fydda i’n ‘neud rhywbeth yn ei gylch e, gewch chi weld, fe fydda i’n rhoi rhawaid o halen yn ei botes e ‘to!

Dw i’n mynd mas gyda Mam bron bob dydd i’r siop lawn silffoedd gwag i aros mewn ciw tu mas i gael dognau. Pethau fel ‘mrkvy, sárgarépák, moron, carottes, zanahorias, carote, möhren, morötter, porkkanat, karóta.’ ‘Sdim digon o fara i’w gael yn unman – ‘kruh, chlěb, pain, pan, pane, brot, bröd, leipä, psomí, chleb’ – mae pobl yn ymosod ar ei gilydd i gael briwsion, a dim ond ychydig o ddŵr ffres sydd hefyd. Wrth gwrs mae’r trydan wedi mynd ers achau, felly mae canhwyllau’n bwysig ofnadw’. Ac eto i gyd dyna’r sielio di-stop gan fortarau.

Mae hi wastad yn bwrw glaw yma, hyd yn oed pan fydd yn heulog, ac ym mhob man mae tyllau enfawr llawn gwaed, a dŵr marwaidd, a llaid. Ac o bryd i’w gilydd mae aelodau’r corff ar draws ac ar hyd. Yn wir, dw i wedi gweld nhw, dw i’m yn dweud celwyddau, w! Cariad yw’r Egni Hollbresennol, medden nhw, ond mae’n edrych fel ‘sai cariad wedi marw, yn fan ‘yn o leia’. ‘Neno Wezir, y newidiwr ffurf chwedlonol, dw i ‘di bod yn darllen amdano, dw i angen trawsffurfio’n hunan rywsut neu’i gilydd, fel y galla i ddianc. Dw i eisiau hedfan bant o faes y gad fel rhyw hen gigfran sy’ di cael llond ei bol ar boen a thranc.

Ond sa i’n gallu gadael ‘y nghartre’, ‘y nheulu, ‘yn ffrind newydd, alla i? O, a dyna’n Mam, a’n chwaer i. Allwn i fyth fyw hebddyn nhw, w! (Dw i’m yn lico fe ormod o gwbl a gweud y lleia pan fydd Dad yn neud i fi deithio, gannoedd ar gannoedd o filltir weithiau, i helpu fe i gyflawni’i fusnes hollbwysig, ma’n gweud. Ma’n teimlo fel ‘sen ni bob tro’n symud o gwmpas, yn ôl ac ‘mlaen. Www, dw i’n sâl môr ofnadwy, ac yn poeni gymaint pan fyddwn ni bant am wythnosau mewn llefydd estron! A ... ma‘na ... stwff arall ... pethau hudol sy'n rhyfeddol a brawychus ... a'r bwystfil ffiaidd yn ffroeni yn 'mhen i ... yn gweud geiriau atgas i fi ... yn trio 'ngorfodi i i frwydro'n ôl a 'nafu pobl yn ofnadw ... pethau fel 'na, ta be, dwi’m yn gallu siarad amdanyn nhw gyda neb ...) [***].

'Drycha, bois, rhaid i fi fynd – ar frys! Dyna'r hen seiren cyrch awyr yn canu ... unwaith 'to! O leia bydd hi'n neud i'r ddraig ddemonig 'na fynd bant am sbel. Wel, nes i ni gwrdd tro nesa – yn ein breuddwydion (neu’n hunllefau) ha ha! – Ta-ta tan toc, mêt!

* * * * * * * *

[*] Cynhwysir y “llythyr” ‘ma wedi’i ysgrifennu gan Daud Pekar at Ffred Llwynlesg yn ôl pob sôn (gweler isod), yn “Cariad, Colled, Chwilod.” Dyw llawysgrif wreiddiol yr epistol dirgel ‘ma ddim yn bodoli wyach (os ‘naeth e ‘rioed – fel sy’n digwydd gyda chymaint o’r “dystiolaeth” grybwyllir yma – er tragwyddol gywilydd a rhwystredigaeth i fi!). Dyma, mynte Ff.Ll. o leia, drawsysgrifiad manwl gywir a ‘naeth e’i hun, er ei fod, wel, yn amhendant iawn wrth geisio cofio’r ffeithiau ynghylch popeth (yn gyffredinol) – ac yn enwedig natur “y gweledigaethau hurtiol od” y cyfeirir atyn nhw yma. (Yr un sylwadau’n union sy’n berthnasol mewn sawl man arall, hefyd.) A rhoi’r ddadl ‘ma i’r neilltu am y tro, dwi’n nodi wrth fynd heibio, gyda gronyn o ddiddordeb (wedi’i gymysgu ag annealltwriaeth gyfartal), debygrwydd y geiriad wrth i’r llythyrwr ifanc tybiedig sôn am ei dad fel “yr hen wrol ryfelwr”, ac am “yr Hen Filwr ‘na sy’n ffrind i Dad [ac ati].” Mae hyn yn bendant yn awgrymu rhyw gysylltiad tywyll, ond alla i ddim deall beth eto. — P.M.

[**] Daw'r geiriau a ddefnyddir yma o lawer o'r ieithoedd a siaradir ar y Cyfandir Gogleddol. Rwy'n gallu enwi'r canlynol: Deyngseg, Dytsieg, Effransieg, Estlendeg, Fyrhlyɡwrhsekeg, Heladeg, Hlownwneg, Italeg, Kaslwyneg, Kimbreg, Lafeysieg, Madgonieg, Madjwngreg, Neyrhlytsieg, Noksikeg, Peɾthehesieg, Podlesineg, Pretaneg, Ronemieg, Rwsikisieg, Sechrineg, Sfeynsikeg, Sikupieg, Slowensituneg, Syrpyskor-fatyskieg, Stylofytsineg, Swlondeg, Tsietsineg, Wrgeinieg.

Does dim amheuaeth bod ieithoedd ym mhob cwr o’r Byd yn newid drwy’r amser. Felly, mae tafodieithoedd oedd ar un adeg yn gyd-ddealladwy’n dod ieithoedd ar wahân gyda threigl amser. Ymhellach, mae’n sicr bod pobl sy’n siarad ieithoedd gwahanol wedi bod yn honni taw’r gwahaniaethau hyn (yn ogystal â lliw croen, credau crefyddol, argyhoeddiadau gwleidyddol, a dysgeidiaethau athronyddol) sy’n cyfiawnhau gweithredu’n filain yn erbyn ei gilydd er pan ddyfeision nhw iaith. (Fel mae fy hen fyti Ffred Llwynlesg yn dweud yn rhywle arall, “Pam bod rhaid i bopeth newid bob amser? Dyw hi’m yn deg, ddim yn deg o gwbl!”).

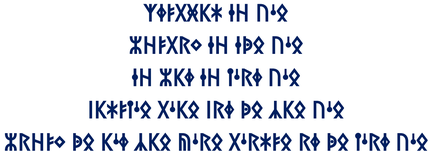

Fodd bynnag, ar nodyn mwy cadarnhaol, dw i’n gallu adrodd y canlynol. O ganlyniad i’m hymchwiliadau i gael hyd i “iaith creu” gan ddefnyddio nodiadau Jack Procter, dw i wedi llwyddo i ail-greu fersiwn posibl ar y "sigla" neu'r glyffiau hynafol a ddatblygodd o system ysgrifennu gyntefig Uthil Zuzas (neu Uza-ma-Dauth). Mae ffurfiau’r llythrennau wedi peidio dawnsio a newid yn ddi-baid ac wedi dechrau crisiali bellach, i fesur o leia. Wedi dweud ‘ny, does syniad ‘da fi eto am eu sain; mae fel petai tyrfa o leisiau o bob math yn moedro, sibrwd, neu ganu yn fy mhen i. Wel, dyma ffrwyth fy llafur hyd yn hyn, ta be:

Dw i ddim wedi datgelu’r Arwydd Ysgarlad Arswydusaf eto (diolch i’r drefn, wedai llawer, yn fy nghyflwr meddwl bregus i), ac ro’n i eisoes yn gwybod yr Arwydd Melyn gwaharddedig. Serch ‘ny, dw i’n credu mod i wedi dod yn agos at ddyfalu ffurf yr Arwyddlun Indigo rhyfeddol. (Fe fydd yr emblemau amryliw’n ymddangos yn unigryw i bawb yn eu hystyried nhw’n gywir, wrth gwrs, os gallan nhw’u dychmygu nhw o gwbl heb golli arnynt eu hunain.) Mae’r weithred o ddyfeisio fy iaith breifat fy hunan yn wir gadw gwreichion y Tân Anniffoddadwy i fyw ynof fi. Felly dal ati a wnaf fi, am fod arna i angen nerth sylweddol i gwblhau’r Gwaith Mawr (a llawer mwy na’r hwn sy ar gael i fi ar hyn o bryd trwy’r sianeli arferol!). — P.M.

[***] Pan dw i’n darllen y rhan ‘ma o hanes Daud Pekar (sy mor anghyffredin o greadigol ac aeddfed i ‘sgrifbin sbrowt mor ifanc nes ei bod bron yn anghredadwy), dyna fi’n dechrau ymgolli mewn lli o ddelweddau. Mae atgofion melys iawn ‘da fi am Galon y Cyfandir, yn dyddio’n ôl i’r amser pan o’n i’n ddim o beth fy hunan, mor hir yn ôl ac mor bell i ffwrdd yng ngwlad anghredadwy Hlîhra (Ilyria, hynny yw). Yn y dirwedd fynyddig ‘na ges i fy magu dan y faner werdd a’i draig driphen, ymhlith y werin oedd yn dlawd ond balch, heini a gweithgar, ond yn eitha twp yn gyffredinol, a siarad heb flewyn ar fy nhafod. Mewn gwirionedd, mae’r Famwlad Aflonydd yr un maint o ran arwynebedd tir â Chimbria ynghyd â Lawaria ac Ynys Blanhigfa yn y Gymanwlad Annibynnol yng Ngogledd Gwlad Meryk. Wedi dweud hynny, mae poblogaeth y ddwy wlad – Kimbria a’r Famwlad – o’r un maint, mwy neu lai, sef tua thair miliwn o bobl erbyn hyn. Glannau Afon Zhêhdhw oedd cartre fy Mam cyn y Cythrwfl Mawr diweddara, a bro fy mebyd, er taw fy hoff le oedd y fforestydd pin o gwmpas Mynyddoedd Duon Ghrâzhghw yn y gorllewin.

Trafaeliwr o’r Gymanwlad Annibynnol oedd ‘Nhad, o deulu Kimbreg oedd wedi gadael Pretania (er bod cryn nifer o bobl wedi defnyddio’r enw Ynysoedd y Teyrnasoedd Anghytûn yn y gorffennol, ac yn ddiweddarach, Gwlad y Cnafon Gwrthun) ar fwrdd y llong ddrwg ei thynged o’r enw Y Ffawd Dda. Arferai fe’i lusgo ei hun drwy’r Ddaear gron gan werthu offer deintyddol i bobl doedd arnyn nhw eu hangen, am ei bechodau, ac roedd wastad yn hoff o gwyno taw “Ymweled ag anwiredd y plant ar y tadau y mae’r Pŵer Anfarwol.” (Er eich gwybodaeth, mae llawer o ddeintyddion mentrus yn byw ar wastatiroedd diffaith y “Wlad Doreithiog” ‘na hyd yn oed heddiw.) Symudais i i wlad fy nghyndadau am sbel ar ôl cwymp yr Anwylaf Arweinydd, ond do’n i ddim yn teimlo’n rhy braf o gwbl gyda’r Freuddwyd Baternalistig, rhwng yr holl blygu glin gerbron y fflag a thalu llw teyrngarwch i Awtocrat Etholedig Holl Wlad Meryk bob dydd, y saethu popeth sy’n symud â gynau, y bwyta mynyddoedd o gig eidion a sglodion, yr hunanddarostyngiad gorfodol yn y Basilicâu Dinesig bob wythnos, a’r hyfforddi i fod yn ddeintydd drwy’r dydd a gyda’r nos, ac yn y blaen, ac ati.

Ffoais i am fy hoedl, sai’n gallu dweud pam yn enwedig. Ac wedyn nes i grwydro yma a thraw ar draws y Gofalfyd (a hala cryn dipyn o amser yn nhiriogaethau gwyllt y Cyfandir Deheuol nas chwiliwyd gan neb), gan ymlafnio i ddysgu celfyddydau seithliw barddoniaeth, meddyliaeth, a ffaneronig, a dwyn cyfrinachau cyfaredd i’r golwg. Wel, daeth drosta i bryd hynny deimlad cry ond brawychus (ar ôl fy arbrofion gyda Lamp Saf-hilé, Carreg Meh-tholé, a Phendil Sath-lafé) y deuai tro tyngedfennol ar fyd ar droad y ganrif a’r milflwyddiant, ac ar ddechrau Oes y Hustwr, y Dyfrwr ar ben hynny. Roedd rhywbeth yn galw arna i, yn y ‘ngorfodi i bron, i fynd i Gimbria, i ymuno, i gymryd rhan yn y digwyddiadau ysgytwol oedd i ddatblygu yn yr Henwlad, mor llawn swynion hynafol ac egnïon arallfydol. Des i felly (gyda help fy ffrindiau Ffredric a Gertrude Llwynlesg) i ymweld â fy arwr Daud, oedd yn grachlenor yn ei arddegau erbyn hynny. Roedd e wedi brwydro hefyd yng Nghalon y Cyfandir cyn ffoi (neu falle dychwelyd) i Aberdydd i gael triniaeth yn y Clinig o’r enw Y Pinwydd am ei anafiadau arswydus. Dyna oedd dechrau fy rhan i yn y stori ‘ma.

Erbyn diwedd y darn ‘ma gan y Pekar ifanc, mae’n amhosib i fi beidio â dwyn i gof y Cyfarwyddiaid Carpiog fyddai’n cropian mynd o dre i dre gan ennill eu tamaid drwy berfformio’r hanesion hynafol i’w cael yn ein chwedlau cenedlaethol “le-Hnêthno al-Êmdlr” (fel aelodau gwallgo rhyw grŵp seiber-esgyniad heddi, fel arfer, y Meddwl Anhreiddiadwy a’n helpo ni!). Ww, mor ddeniadol a gafaelgar oedd y straeon (ac maen nhw’n dal i fod felly)! Fy hoff un i ydy “Sut Achubodd Zrênthí Vêydjrow y Famwlad a Distrywio’r Byd.” Ro’n i’n hoff iawn o gwmni crwydrol o’r enw “Y Storïwyr Simsan” (dan arweiniad – os gellir ei alw felly – Sâro se-Mŵnki), a dyma fi’n adrodd eu fersiwn i chi nawr. Os ydych yn eistedd yn gyfforddus, byddaf yn dechrau.

“Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw, neu Ifan Ddybryd â’r Enaid Milain, mab i se-Vâhlw Hâymarks Trŵvlad, hynny yw, y Gwerlin Harri Hendref, Rheithor yr Uwchdiroedd Geirw, oedd plentyn cydnerth dros ben, ac anfad tu hwnt. Roedd y Tad wedi lladd ei wraig mewn gwaed oer cyn gynted ag y ganed y bachgen. A’r Gwerlin a laddwyd yn ei dro gan Vlâvw den-Dhêrah, y Famfaeth Ryfelgar, a ddaeth yn warchodwraig awdurdodus dros y crwt a’i dirmygai hi â phob mymryn o nerth oedd ynddo. Se-Dhômeh, y Frehyres Ecsarch, oedd yr enw ddewisodd hi, ar ddechrau’i Theyrnasiad Braw, fyddai’n para am ryw un flwyddyn ar bymtheg. Fe sefydlodd Vlâvw unbennaeth haearnaidd ble llywodraethai fel Meistri mwya milain Théybē gynt. Fe fyddai’n codi arswyd ar y werin, eu hecsbloetio, eu defnyddio fel porthiant i’r gynnau mawr yn ei rhyfeloedd ymosodedd a choncwest diderfyn, a gadael i’r goroeswyr newynu a marw o heintiau ofnadwy a ddyfeisiai hi’i hun. Ac er bod y boblogaeth yn ei chasáu hi, ro’n nhw’r rhy eiddil a churedig i frwydro yn ôl. Ar ben hynny, meddai hi ar “hôrzhkadhve” neu “arswyd-sgôp” yn cynnwys hylif du byw wedi’i animeiddio gan fflam wyrdd dragwyddol, dyfais a ymddengys a gweithio’n unigryw yn unol â mympwyon ei meistr, ac a’i gwarchod rhag niwed gan bob grym meidrol.

“Er mwyn tawelu Dhvâno a’i reoli, ychwanegai den-Dhêrah lwydni gwanhaol i’w brydau bob dydd, ac oni bai am ei gryfder arallfydol, byddai fe wedi gwallgofi, ei niweidio’i hun ac eraill, a marw. Ond yn lle ‘ny, dim ond cynyddu’i ddychymyg byw a wnâi’r sylweddau seicedelig naturiol yn y bwyd, gan ei helpu i ddianc o’r realiti ffiaidd o’i gwmpas a goroesi, ar ryw ystyr o leia. Wedi dweud hynny, roedd pob awr o’r dydd a’r nos, naill ai ar ddihun neu’n cysgu, wedi’i phlagio gan freuddwydion gwyrthiol wedi’u cymysgu â hunllefau iasol am ryw Blaned Bell o’r enw se-Zêhlvado, Nova Terra, y Ddaear Newydd. A bod yn onest, roedd e’n teimlo doedd e ddim yn byw yn y byd go iawn o gwbl ran fwya’r amser, a dirgelwch llwyr iddo oedd p’un ai mynd neu ddod yr oedd e. Âi hyn ymlaen nes i’r bachgen gyrraedd oedran oedolaeth, sef pymtheng mlwydd oed yn yr Uwchdiroedd Geirw.

“Y pryd hynny, dechreuodd Dhvâno glywed llais yn galw arno. Er ei fod yn isel ac anodd ei ddeall ar y cychwyn, po fwyaf astud y gwrandawai arno, mwyaf clir, a thaer yn y byd y deuai. Dan ddylanwad y Llais o’r Tu Draw, fe fyddai’n rhedeg bant i hen sied ar gyrion y cadarnle â mur o’i gwmpas. Yno, roedd iâr ddu annwyl â llygaid aur o’r enw Zrêndhw yn byw. Ac yno hefyd, deuai madfall enfawr felyn â llygaid fel gafr o’r enw Nîvdezh i lechu yn y cysgodion. Yn ola, roedd y bachgen dyfeisgar wedi denu i gaets gath goed albino ac iddi lygaid coch o’r enw Ghôhrw. Fe âi Dhvâno bob dydd i fwydo ei angyles bluog â ffrwythau, llysiau a bara wedi’u benthyg o’r bwtri; ei ddraig gaos â chynrhon y blawd, morgrug, a chrics a gâi gan hen bysgotwr dall yn byw mewn cwt dim ar bwys Afon Zhêhdhw; a’i ddiafol blewog â chigach a seimiach gan y gogyddes y lladdodd yr Unbennes ei gŵr mewn pwl o dymer ddrwg. (Roedd y sièff yn methu diodde Vlâvw a dweud y lleia, ac fe fyddai hi’n helpu Dhvâno mewn ffyrdd pwysig eraill yn nes ymlaen hefyd.) Pryd bynnag byddai’n bosib, âi fe ag aeron, blodau, a nytmeg er mwyn addoli pwerau anwahanadwy’r nef a’r uffern – a’r anrhefn sy’n rheoli dros y ddwy – a gweddi am ryddhad o’i gaethwasiaeth. Naeth y bachgen colledig benderfynu taw Zrênthí Vêydjrow oedd enw’r endid annaearol a ymgorfforai yn y drindod hon o afatarau.

“Aeth y fath gastiau ymlaen am fis ar ôl mis, ond roedd llygaid den-Dhêrah ym mhob man yn gwylio’r plentyn, ac un dydd naeth hi ddanfon gwas bach i ladd yr iâr a dod a’r corff iddi. Wedyn naeth hi drefnu iddi gael ei choginio a’i rhoi o flaen y Meistr Ifanc, a, dan grechwenu a thynnu ystumiau, wrth biffian chwerthin a glafoerio, i gyd ar yr un pryd, yn y ffordd fwya arswydus, naeth hi fynnu iddo fe fwyta. Pan wrthododd e, heb ddangos dim emosiwn o gwbl, naeth hi’i orchymyn iddo gael ei garcharu yn y Neuadd Gron Aflawen adfeiliedig ar ei ben ei hunan bach am benwythnos. Ond, mor gryf oedd ei ewyllys, a chymaint ei gasineb, nes iddo ddal i weiddi yn ei feddwl ar Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Yr Ystelciwr rhwng y Sêr, oedd bellach wedi dod yn dduwdod a gwarchodwr iddo. A dyma’r hyn roedd e’n ei ddweud wrtho dan grochlefain nerth ei ben: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Arglwydd Popeth, gwnewch ddim ond yr un peth hwn i fi eich mab!’

“O rywle anhysbys, daeth y Tywysog Anaeddfed o hyd i ryw nerth sylweddol o ran corff ac enaid. Pan ddaeth e mas o Anheddfa'r Gromen Adfeiliedig o’r diwedd, aeth e’n syth i gasglu planhigion o bob math, yn cynnwys blodyn yr enfys, calchlys paniglog, calmia llydanddail, codwarth, daffodil, dail tybaco, ffion, gellesgen, gold, gwaedwraidd, lili’r dyffrynnoedd, lili’r fenyw bert, llysiau’r blaidd, milddail, oleander, tegwch y bore, tiwlip, a throed yr ehedydd. Wedyn, sleifiodd bant i ymweld â’r gogyddes gyfeillgar, a rhoes hi bump o’r rhain yng nghinio den-Dhêrah y noson honno. Ond hyd yn oed wedyn, bwytodd hi’n awchus, gan ddannod y bachgen – cyn syrthio ar lawr dan wingo, malu ewyn, a byrlymu’n ddryslyd. Roedd hi wedi llyncu cymaint o gyffuriau yn ei bywyd ofnadwy fodd bynnag nes iddi ddod at ei choed yn eitha buan. Cyn gynted ag y gallai hi siarad, rhoes hi’r gorchymyn i Dhvâno gael ei gloi yn y ddaeargell ddyfnha heb fwyd na dŵr am dridiau a theirnos nes y byddai bron iddo ddarfod. Er gwaetha’r trafferthion oll, fe ddaliai fe ati i erfyn mor daer, drosodd a thro: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Arglwydd Popeth, gwnewch ddim ond yr un peth hwn i fi eich mab!’

“Pan gaeth y llanc ei ryddhau o’r dwnsiwn tywyll a rhewllyd o’r diwedd, roedd e mewn cyflwr gwael. Baglodd e bant a chael ei dendio gan wraig hysbys yn byw mewn hen felin faluriedig ger y Pwll Corsiog. Rhoes iddo fwyd a dŵr, a dweud wrtho taw coch tywyll oedd ei awra, hynny yw lliw rhyfelwr; taw rhyw bŵer eithriadol oedd yn ei warchod; a taw fe fyddai’n arweinydd mawr. Ryw wythnos yn ddiweddarach, aeth den-Dhêrah mas eto, cipio’r fadfall felen, a’i llindagau â’i dwylo’i hun, cyn cael troi’r croen helaeth yn bâr o sliperi moethus. Pan naeth y Famfaeth sioe o’i hun o flaen y llanc, ni ddwedodd e’r un gair, ond llamu arni a’i thrywanu yn y goes hyd at yr asgwrn â chyllell blatinwm. Y tro hwn roedd Dhvâno wedi ychwanegu chwech arall o’i blanhigion i fwyd yr hen wrach. Ond ar ôl hopian o gwmpas y stafell fel mochyn llawn ysbrydion aflan dan sgrechian a bloeddio, llwyddodd hi i dynnu’r llafn o’i aelod cyn syrthio i gwsg aflonydd am bedair awn ar hugain. Pan ddeffroes hi, naeth hi orchymyn i’r bachgen gael cweir iawn. Ac yn wir, bu ond y dim i ymgreinwyr y Din Cwartsit ei guro i farwolaeth. Hyd yn oed wedyn, ni ildiai’r llanc, a sibrydai dan ei ddannedd yn ei loes: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Arglwydd Popeth, gwnewch ddim ond yr un peth hwn i fi eich mab!’

“Gwellodd Dhvâno yn hynod o gyflym, fel petai drwy ryw hudoliaeth annirnad. Sawl dydd ar ôl hynny, dyna fynd den-Dhêrah allan unwaith eto i archwilio’r gwichian uchel digon i oeri’r gwaed yn dod o’r sied. Yno fe naeth hi ddarganfod y gath fferal ar fin newynu. Ar ôl brwydr ffrochus, llwyddodd hi i dorri gwddf y greadures, wrth gael ei hanafu’n wael gan ei chrafangau gwenwynig ar yr un pryd. Aeth hi’n ôl i’r Mans yn waed i gyd â chelain waedlyd y gath a’i thaflu ar y bwrdd o flaen y bachgen. Y tro hwn roedd Dhvâno wedi ychwanegu saith arall eto o’i blanhigion i fwyd y gythreules waetha wrth iddi fod ar ei phethau enbyd. Tra oedd hi’n sglaffio’i chinio dan regi a glafoerio fel menyw o’i cho, mor ddolurus oedd y briwiau fyddai byth yn gwella, dyna Dhvâno yn taflu olew tra fflamadwy drosti, a’i rhoi hi ar dân â channwyll. Digon i ddihuno’r meirw oedd y cythrwfl a ganlynodd wedyn. Ond, ar ôl yr holl ymdorchi a’r melltithio, diffoddodd den-Dhêrah y fflamau, er bod ei chnawd wedi toddi fel gwêr.

“Roedd Vlâvw den-Dhêrah wedi llofruddio’r tri chreadur sanctaidd, Zrêndhw, Nîvdezh, a Ghôhrw, gan berfformio aberth rhyfeddol heb yn wybod iddi’i hun. Deirgwaith roedd Dhvâno wedi trio’i lladd a deirgwaith roedd hi wedi goroesi a dod yn ôl yn fyw. A nawr, yn debyg i anghenfil chwedlonol, roedd hi’n moyn dial terfynol ar Dhvâno, y maethfab llofruddgar, gwrthnysig, anniolchgar. Er gwaetha’i chlwyfau oll, naeth hi orchymyn i Dhvâno gael ei hongian mas o ffenest y Tŵr Firidian wrth ei freichiau am ddydd a nos, cyn cael ei labyddio. Ond hyd yn oed wrth iddo gael ei lusgo bant wrth y fferau, roedd e’n llafarganu yn ei ben: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Arglwydd Popeth, gwnewch ddim ond yr un peth hwn i fi eich mab!’

“A dyna beth ddigwyddodd wedyn. Wrth i’r bachgen grogi ar y Tŵr Firidian, dyna fe’n crefu ar y dorf nychlyd, anobeithiol a gasglodd i edrych yn gegrwth ar yr olygfa druenus, fel y canlyn: ‘Fi sy ‘di darganfod y gwirionedd. Artaith fu’n holl fywyd i hyd yn hyn. Ond, ymysg y sarhad, a’r coegni, a’r dioddefaint dw i wedi gweld y dyfodol. Does ond rhaid i chi aberthu’ch plant i Zrênthí Vêydjrow – duwdod plu, a chennau, a blew, sy’n feistr ar fyw, marw a thrawsffurfio, ac yn dwlu ar waed, a chwys, a dagrau – i newid y Byd. Os newch chi hyn ganol nos heno, a’r Haul wedi marw wrth i’r Lleuad guddio’i hwyneb, gewch chi’ch achub rhag y parasitiaid sy ‘di bod yn ysglyfaethu arnoch am ganrifoedd!’

“Wrth reswm, doedd y bobl ddim mor dwp ag i gredu’r fath rwtsh, ond ro’n nhw mewn cyflwr mor alaethus nes y bydden nhw wedi neud unrhyw beth bron i wella pethau i’r graddau lleia. Felly, naeth y rhan fwya ohonyn nhw fustachu dringo lan i doeon gwastad eu tylciau o dai wedi gwisgo o’r corun i’r sawdl mewn glas tywyll, lliw galar, gan gario talpiau mawr o sialc ac o glai wedi’i grasu, a llawer ohonyn nhw wedi'u ffurfio, yn amrwd neu'n fwy gelfydd, yn ddelwau a cherfiadau o'u plant. Am hanner nos, yr Haul wedi marw a’r Lleuad yn cuddio’i hwyneb, naethon nhw frathu babanod Dlôkda Lotké â dagrau, a thaflu plant Djŵkhta Swtach i’r llawr dan udo a griddfan. Wedyn aethon nhw i’r gwelyau i gysgu fel moch cyn deffro i artaith bywyd dan draed y Famfaeth Ryfelgar unwaith ‘to. Ac yn yr awyr fwll boeth y clywid Llais Trallodus yn datgan heb ball yr hen litani: ‘Zrênthí Vêydjrow, Arglwydd Popeth, gwnewch ddim ond yr un peth hwn i fi eich mab!’

“Y dydd nesa, ymddangosodd Vlâvw den-Dhêrah, gan guddio’r cnawd ysig wedi’i hagru gan greithiau a chrach dan gŵn hir llwyd, a chwfl dwfn am ei phen a mwgwd dros ei hwyneb, er mwyn cosbi a chael dial ar y rebel ifanc, a chael gwared arno unwaith ac am byth. Ond roedd Zrênthí Vêydjrow wedi clywed gwaeddau brwdfrydig y werin bobl a derbyn eu haberthau ffug. Gan gofio'i ach a'i chasáu, ymrithiodd yn gynta ar ffurf draig driphen, ei thair cynffon a’i thri phen fel cath, ei chyrff fel madfall, a’i esgyll fel iâr, a phlu, a chennau, a blew ymhobman – ac ar unwaith ddechrau trawsnewid i fod yr ymgnawdoliadau mwya aflednais a di-chwaeth. Roedd den-Dhêrah ar fin gwthio’i dagr du, danheddog a miniog iawn o gallestr gaboledig yng nghnawd Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw i’w iselha fe gerbron y bobl cyn iddo gael ei labyddio i farwolaeth (am y credid taw amhûr oedd gŵr a fu farw yn frwnt ei gorff heb fod ar faes y gad, ac y câi fe ei gludo ar ei ben i ddiodde gwewyr yn Pwll Diwaelod am byth). Ond disgynnodd y ddraig arni fel piler o dân gwyn a cholofn o gwmwl du, yn berwi o waed coch a bustl melyn. A dyna oedd hi’n amsugno’r elfennau erchyll, a chael ei llenwi ganddyn nhw, a chwyddo, wrth i’w chorff anffurfiedig ddirgrynu fwyfwy.

“Deirgwaith roedd Dhvâno wedi trio lladd den-Dhêrah a deirgwaith roedd hi wedi goroesi a dod yn ôl yn fyw. Deirgwaith yr oedd Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw wedi’i gosbi a’i fychanu, a deirgwaith yr oedd wedi ymaros a thyfu mewn grym. Tri anifail glân a laddodd y Frehyres Ecsarch mewn aberth damweiniol, a phob un o’r tri a oedd wedi’u hailgyfodi (ond nid yn y modd arferol, wrth reswm). Ac o hynny ymlaen, priodoleddau hudol fyddai i’r rhif tri a phopeth wedi’i gysylltu â fe. Beth bynnag am hynny: yn awr roedd i’w clywed hyrddiau o biffian amhwyllog, ac osôn, siarp ac egr yn llosgi’r ffroenau, wrth i ffagliad o indigo ac uwchfioled ddallu bawb.

“Ymhen ychydig o amser yr oedd corff y Faethfam Ryfelgar yn crynu fel petai cerddor uffernol yn ymhyfrydu mewn distrywio’i offeryn. Ac yn fuan roedd yn ysgwyd fel petai anghenfil anweledig yn ei phawennu’n andros o erwin. Yn y pendraw, pob gronynnyn yn y bêl gyfoglyd o gnawd yn grwnan a naeth benderfynu dod oddi wrth ei gilydd, a dianc i neud drwg ble bynnag y gallai ar ei liwt eu hun Ac felly datgorffori oddi mewn a wnaeth den-Dhêrah o’r diwedd, ond nid yn rhy fuan, ymhlith cymylau o arsin, batrachwenwyn, botwlin, clorin trifflworid, seianeid, hydrogen sylffid, risin, sarin, a strycnin. (Mae ‘na rai’n clepian hyd heddi am sut agorodd rhyw fath ar Hollt Befriog yn y Nefoedd y pryd ‘yn, a gweddillion marwol den-Dhêrah yn cael eu sugno drwodd.) A dyna lle’r oedd se-Vârkha, y Byd-frenin newydd, yn datgan ei siant fuddugoliaeth:

|

“‘Dhra zhla Zrênthí Vêydjrow kha; Ghŵdjo dlândai dhlêdhra shvâni le hvêkhai dhlêdhra kha. Shlŵdhra mbŵloi ha dhlêdhra khlîgha dhle kha, Kdŵlo blw nlâla dhlêi kha. Ngŵlo Zrênthí Vêydjrow ŵa kha!’ |

“‘Allan yr â Zrênthí Vêydjrow; Duon ei feddyliau, cochion ei enau. Daw ef â thranc i’w elynion, Er iddynt ymbil am hedd. O Zrênthí Vêydjrow Ffyrnig!’ |

“Ni ddioddefai Zrênthí Vêydjrow Ffyrnig (pwy, neu beth bynnag oedd hwnnw) gael ei gwatwar, fodd bynnag, na’i gwahardd rhag derbyn yr aberth priodol, chwaith. Yr unig eiliad y naeth Vlâvw den-Dhêrah sychdarthu, diflannodd pob plentyn yn yr Uwchdiroedd Geirw, ac yn ei le safai (neu orwedd, neu eistedd) cerflun o’r crwt, wedi'i neud o sialc neu glai wedi’i grasu, ac yn gwisgo gŵn gwaedrudd aberth. Ac roedd pob delw'n berffaith, ar wahân i'r ffaith nad oedd ar yr un ohonyn nhw wyneb o gwbl (na phen, a bod yn onest, o bryd i'w gilydd). Ble aethai’r plant, neb a wyddai byth, a dilynodd cryn lefain a churo’r fron go iawn. Ond un peth oedd yn sicr. Pryd bynnag byddai farw un o’r babanod neu’r bobl ifanc ymhlith y werinos o hynny ‘mlaen, byddai’r hynafgwyr a’r hynafwragedd yn mynd â’r corff ymaith yn syth, a thorri’r pen, a’i roi fel aberth priodol ac amserol i’r duwdod dialgar a nerthol iawn Zrênthí Vêydjrow mewn seremoni anhraethadwy.

“Wedi datgorffori corpws sylweddol y Faethfam Ryfelgar, doedd y mater, na’r egni, na’r dirgryniadau oedd ynddo yn y lle cynta (hynny yw, y dymuniadau, y bwriadau, y bersonoliaeth, yr ewyllys, a’r ysbryd hyd yn oed, yn ôl rhai) ddim wedi diflannu. Aethon nhw yn eu blaenau i ddylanwadu’n wael ar deimladau, meddyliau, ac ymddygiad pob endid yn bodoli ledled y Bellen Bechadurus o hynny ymlaen. Aeth se-Vârkha Dhvâno Dâjvowdh Vlâdhvadlw, y Byd-frenin Ifan Ddybryd â’r Enaid Milain, Pontiff yr Holl Fyd, allan hefyd, i goncro, a difa, a chaethiwo yn enw Zrênthí Vêydjrow, yr Ystelciwr rhwng y Sêr. Yn ei falchder, ei anhrugaredd, a’i gamgrediniaeth, enillodd gasineb yr Eglwys Bondigrybwyll. Ond ni hidiai Dhvâno Dâjvowdh affliw o ddim am hynny, ac mewn gwirionedd, ymhyfrydai yn yr enw drwg oedd arno, yn enwedig o wybod bod ganddo arswyd-sgôp neu hôrzhkadhve bellach i’w amddiffyn rhag niwed gan fodau cyffredin dan bron pob amgylchiad arferol o leiaf. Ac er mai Zrênthí Vêydjrow a arweiniai feddwl a chorff Dhvâno, fe hawliai’r Ystelciwr rhwng y Sêr ufudd-dod llwyr yn gyfnewid am ei nawddogaeth ysgeler. Felly nid caru y byddai Dhvâno fyth, na chael ei charu chwaith, a Zrênthí Vêydjrow a bennai le ac amser ei ddiflannu o’n Cartref Calonrwygol ni maes o law, gan adael dim ond talp enfawr o lo ar ôl.

“Yn y diwedd, esgorodd gwerin brofedigaethus y Famwlad ar fabis newydd wrth gwrs, ymysg y cymhelri, y tân, y gwaed, a’r sgrechian ingol diarbed. Ond er cryn fraw iddynt, roedd â phob plentyn newydd-anedig groen fioled (ar bod hwn yn cael ei gannu’n ddigon buan), yn ogystal â nodweddion ryw anifail neu’i gilydd, fel cynffon neu bawennau cath; crib, tagellau neu blu iâr; llygaid neu cyrn gafr; cennau neu tafod madfall, er enghraifft. Fe fyddai’r rhain yn eu didoli nhw oddi wrth y rhieni, a ddechreuai eu hofni, a’u gwahanu oddi wrth weddill y Dhrônlw, hynny yw’r Ddynol-ryw, a ddeuai i’w ffieiddio. Dyna hefyd oedd dechrau’r fasnach lechwraidd mewn pethau o bob math (yn cynnwys sylweddau, arteffactau, ffoaduriaid, a syniadau) rhwng y proliaid o dan erledigaeth yn Hlîhra a’r rhai yng Nghimbria (yn ogystal â’r anwariaid mochaidd ar y Cyfandir Deheuol diystyrllyd).

“A’r gynnen, y cieiddiwch a’r tywallt gwaed yng Nghalon y Cyfandir Gogleddol a waethygai, ac ymledu i wenwyno pob cwr o’r Sffêr Sâl, dan faner werdd y Ddraig Driphen. Tra anobeithiai Archimandriaid yr Eglwys Ffug wrth ystyried lledaenu Heresi’r Annatrys ac Anorthrech Dri yn Un, chwarddai se-Vârkha Dhvâno fel dyn o’i gof, ac arhosai Zrênthí Vêydjrow yn hollol galon-galed yn ei ddymuniad am ddioddefaint a dinistr. Felly, y rhyfel rhwng y ddwy garfan a barhâi (er gwell neu er gwaeth), gan ddarparu eneidiau yn y Gorddwfn Gresynus (neu’r Pwll Perffaith yn ôl yr ochr arall) am oesoedd diderfyn oddi ar hynny. Ac mae’n para o hyd heddiw, a’r Ddaear Ddrwg yn llefain dagrau o waed wrth iddi gyflymu at ddifancoll, pan foddir hi mewn afonydd o hylif du cyn cael ei hysu mewn tân gwyrdd tragwyddol. Pob clod i Zrênthí Vêydjrow!”

Felly dyna chi wedi’i gael ar ddu a gwyn, os nad o lygaid y ffynnon ei hun – dw i ddim wedi clywed Y Storïwyr yn perfformio ers dyddiau fy llencyndod. A, tecaf fro, bro mebyd! Y chwedl enwog am sut y daeth Hlîhra i fod yn darddell ac uwchganolbwynt i’r casineb diwaelod a’r gwrthdaro di-baid yn ymledu dros gramen shw-Zêha Hrôzhdha, y Sfferoid Syfrdanol hwn. Mae’n esbonio pam bod tri’n nifer nerthol; pam bod plant a enir yng Nghalon y Cyfandir mor gryf, a rhyfedd, a llawn doniau hudol; a pham bod y fath elyniaeth filain yn bodoli rhwng Comisariaid rhyng-gyfandirol yr EFE a Phengolliaid Ilyria. Wedyn dw i’n dechrau meddwl amdana’n hunan a’n hanes i, ac er mod i’n gwybod mod innau’n hanu o’r dras unigryw 'ma (yn rhagorol neu'n iselwael yn ôl safbwynt dyn), dyna fi’n crynu o ystyried taw o bosib na alla i chwarae rhan – trwy anfedrusrwydd neu drwy amharodrwydd – mewn helpu i ail-lunio’n bodolaeth ddagreuol a dod â’r Ddaear Newydd i fod, yn yr oes sydd ohoni.