Tall Tales 13 Realizing

From: The Endless History of the Holiest World-Wide Church

Uthil Zuzas would not allow Rev-zilé to leave, inviting her to materialize inside a sphere of black hornblende that he then wrapped in a thin layer of silver so that she could not escape. And there she stayed, ranting and roaring, betraying a great many secret words, before she shared the secret of writing with him. And that is what she did at last, but unwillingly, and whilst cursing her words as she said them, completely contrary to her revelation to Nilroth from the burning pomegranate tree. Uthil Zuzas insisted on having this tool to promote the development of society and expand his influence [*]. He saw that he could create a permanent record of his greatness, his laws, his doctrine, and his perfect social order for generations to come, even when the people’s memory had shrunk to nothing. Documents created by him, containing established sacrosigns, and strong symbols, would be much better than an arbitrary, oral record, which always changed and died like a living creature. With writing, he would cut a path from the pitch-black bog created by the tongue’s enchanting strength, which beguiled listeners with the promise of pristine discernment, but then deceived them and confused their feeble minds. And so Uza-ma-Dauth would be his name. It is he who would possess the Language of Heaven, and he who would control it, and command it, and use it, in its immaculate and unchanging purity.

From: Love, Loss, Coleoptera

And although I didn’t want to do it, I had to stare at her. I then saw that her face was the familiar face of my poor Mum, whom I loved so much, until she went; and even more, then. That moment, I felt so lonely, so full of longing, the images around me were so thick and strange, and my heart broke. But as soon as I had grasped who was there before me, I went into a panic to see there not the ashen face of a sick woman dying of wasting disease, but first the visage of an exceedingly beautiful princess with black gloss on her perfect lips, and then the image of a highly dignified and harsh old woman in the bloody uniform of a nurse. I was shaken to the core from realizing that I was in the presence of the Triple Goddess herself. And then – my heart almost stopping – there appeared my own face, filled with fear, and rage – and hate. Immediately, as the dawn begin to break, I was snatched far away to the very top of the keep.

He saw himself as a technologist building a perfect explanatory machine, which would follow the text’s sober and abstract blueprint to overcome the failings of natural spoken utterance. He would become Parent of the Nation; the founder of a sacred tradition; the source, disseminator, and arbiter of truth; and the sustainer of state power down through the millennia. He would break the link between the oppressive authority of the degenerate biological family and the servile obligation of the children, and rend the chain binding the master’s unearned honour to the blind dedication of the pupil. Furthermore, permanent inscriptions would form a very close link between the living and the dead, between the security of the past and the possibilities of the future. And so, they started building Houses of Rebirth and filling them with the strange and powerful holy glyphs that they loved and feared at the same time.

And then I extended my arms to oppress the Cruel Eyrth, as threads of darkness and light sprang from my body to connect me with everyone and everything in the Two Worlds, like an umbilical cord linking mother and baby. And, Ooh, it was such a great feeling! I had jumped into the void, hoping to be annihilated, but instead had been rescued, or saved – but for what purpose in particular? Then, there opened in front of me a completely black square, and around it, on emerald mountains, chimeras consisting of blood-red wolves, purple lions, indigo tigers, and a white dragon burning everything with sweet flames.

But the writing became a trap and a nightmare for Uza-ma-Dauth, since he finally came to believe that his ideas were completely worthless if they had not been written down, and broadcast, and read by others, and indeed by all the Cruel Eyrth. And as he scribbled more and more, and as more people swallowed the words without the author being there to control the process and prevent an incorrect reading, they began, as usual, to pronounce the words with their own unique intonation, and change them, and worse, they persisted in analyzing for themselves. And then, without the master’s authority, they would devise completely opposing interpretations, and let themselves see suggestive, debased, and fascinating meanings in the texts, and create fanciful stories from them.

I floated then for ages, it seems, sailing over the All-World on a flying bed. Whilst searching in the Southern Reach, near the Dog Star, for hidden information about dissolving fear and commanding love, I thought, “Never ever wake me from this sleep. But be sure that as I have strolled the path of the stars, meditating, so also I have been weeping uncontrollably.” Maybe I reached Muze-mara by chance, visiting Ví-aza’s vast polymorphous polyhedron. Wherever I was, I found some organic annihilation engine, or some transformation machine. Because I didn’t know what I was doing, I was enchanted by it, and I called it down to lie like a syringe stuck fast in the addicted World’s flesh. Although I did this, where it had come from, or even what it really was, is still a complete mystery. But sometimes when you open doors, unexpected and unwanted things get through, I learned to my own cost.

And as other people heard the stories in their turn, they began to gather random meanings to make sense of the materials already in existence. From the public discourse came mythology, and from this came ideology, one faction using the words as a basis and excuse to belittle, harm, or exterminate the other. The written word, which was originally supposed to be a source of law, a repository of medication, and a means of salvation, also became a curse, poison, and scapegoat for numerous evils. And so too was magic born, a small, dumb monster, without a species or particular form, but terrifying, especially because of its ability to achieve all its aims without qualms. And woe betide them! The first act of the new regime was a perversion of justice. Behold the Warlike Foster-mother from the old legend who killed her husband the Vicious Mime-artist by telling him jokes until he laughed himself to death. And then she was defended by the Burlesque Clown from the Absurd Circus who used the freedom of the mask and the make-up to juggle with language, persuading the court that it was not possible for anyone in their right mind to believe that words could harm someone. And so, she was acquitted of all charges, and went on to murder the King, and then, many years later, to wreak havoc over the whole of the Cruel Eyrth.

And I had summoned it, and switched it on, or woken it up, so that it made itself known and poured out its digestive juices to feed on the World, or to embrace it, maybe, in its own way. Like a living scrying-screen, it had mockingly started sucking in whatever stood so meekly in front of it, becoming like it, and imitating it using the raw materials around it. How, or why, it acts to achieve its aims, and what these are, I’ll never guess. It’s like a parasite forming such a perfect symbiosis with the Host Planet that it merges completely with it, playing a ghastly game whilst mashing and distorting everything it creates in its Brave, New World.

And behold! This is what will happen if one strays from the orthodox path of goodness. Gradually, over the millennia, the Nava-thalí tribe grew bored with segregating themselves from the rest of the Cruel Eyrth, performing the rituals, and keeping the sacred candle burning in the House of Rebirth in the huge ziggurat in the heart of the city. And woe betide them! The members of one caste did work appropriate to those of other castes, defiling themselves abominably. And as soon as the holy flame shivered and went out for the first time in centuries due to the unfaithfulness of the Nava-thalí, the ranks of the Despot of Nin-vethí shattered the walls of their city, and bore them away to Aliz-íya. And there, the Del-hurí was the natives’ name for the exiles. And they suffered desperately, weeping, and wailing, and gnashing their teeth, when they were not working their fingers to the bone in the salt-mines, which were almost bottomless, and extremely hot.

Still under the intoxicating influence of the potion, and not really cottoning on to what I was doing, I wrote a letter to whoever might find it in the future, putting down my ideas and explaining what was driving me on. When I sobered up, later on, and came back to Hellsgate, I hid it somewhere without reading it. I felt that they were still laughing at me, somehow, the Old Otherworldly Gods, seeing me still alive, but in wretched pain all the time because of my wounds. I saw then that I hadn’t died in the first place, and so, well … They were extremely cruel, and were playing horrible tricks on me. Or maybe they didn’t give a damn at all. But for sure, one thing I did know – my lame attempts at doing magic had nothing at all to do with this complete cock-up.

And there only one of them called Tho-vítha from the Nava-thalí tribe kept the law of Uthil Zuzas in its true form, despite the order of the City Masters, stealing the exiles’ corpses and dissolving them in sacred acid. When his wife died after eating one pip from a peculiarly pungent pomegranate she had pilfered from the Princess’s Pleasure-park, Tho-vítha cremated her on top of an open tower, reciting, ”Behold the Daughter of Pain, thrown into the fire in the hand of Victory in the hateful land of Aliz-íya. The law requires that one put the dead in the blasted soil where they fall. But this foreign bird, crown of the folk of Thali-himila, shall never be interred, but she shall escape again as is her wont.” The Masters were not pleased to hear this at all, and they accused Tho-vítha of murdering her. As a punishment, he was blinded by a flock of black doves and white crows, who ripped his eyes out as he prayed for salvation, before he was driven out from Nin-vethí to die in the great, red desert beyond the walls.

So, I’m dead sorry, I know that all this guesswork is unfinished and muddled. But despite the all the shortcomings, I hope it’s not for nothing, by the Indolent Idolaters! Having said that, my magic gadgets aren’t working anymore, my spells are broken, and I don’t have any real answers since I can’t bring myself to ask the ugly questions. It is as if there’s a door in front of me, and it's ajar, and there’s loads of amazing treasure the other side of it, but also some loud noise like wild animals in the blackness inside.

There, in the great, red desert, the Cosmic Power appeared to Tho-vítha in the form of Rev-zilé. If he had been able to use his eyes, he would have seen that she was standing on the Crescent Moon with a flock of red butterflies that quickly turned into tiny birds flying around her, and a circlet of stars on her head. She was untying knots in a long, purple ribbon, as her feet trampled a snake curled beneath her, and a large, yellow lizard to boot. Rev-zilé told him, ”The bond of disbelief has been freed by the obedience of your faith even in a strange land. Go with me to Ev-thana, where a demon called Az-mothus is killing all the bridegrooms on their wedding-nights!” Tho-vítha agreed as he had no other choice. And on their way there, Rev-zilé told him to catch a fish, and cook it. Tho-vítha did so, and with the help of Rev-zilé, he discovered that the fish’s boiling bile cured blindness, and that a paste containing the heart and liver would cast out demons.

I need to stare at whatever’s there amongst the squalor and the stench, but I’m not strong enough, and step back gingerly, closing the door and sneaking off. I’m appalled because everything’s so crazy and senseless, and I know there’s no way to win a game if you’re playing without a full deck of cards. But here I am shouting with all my heart that the things driving me on aren’t selfish, and I’ll keep on trying to change the Cruel Eyrth with the parties, and the music, and the Big Message, and so I’m not giving up hope just yet.

Tho-vítha cured himself of his blindness, and went to Ev-thana to cast the demon out. He could then see, although he did not have eyes in his head. When they reached Ev-thana, Tho-vítha did that. And then he married Ze-ríya, one of the brides who had lost her lover, and settled there, on top of a mountain called Ek-lesya, and became extremely rich, by selling ready-made potions of all kinds that he concocted with the help of Rev-zilé. And so, they declared their good deeds, and worshipped, and gave praise, and fasted, and gave alms, in accordance with the teachings of Uthil Zuzas, and the luxurious house at the top of the mountain became a shrine, and then a temple. And after that, Ek-lesya would be the name of every temple, shrine, and house of worship. And a message went back to the exiles in Nin-vethí in Aliz-íya because of that.

But, every night, the demented beast that wants to possess me lets me know it still reigns over the Vale of Rushes. This is the Walker in Darkness from whose face Heaven and Eyrth fled ages ago. Its fingers are extremely long. It makes a gurgling, choking, howling sound, like its countless fangs are all being wrenched from the gums then and there. The red eyes with no whites shine, full of blood. It stretches its limbs so very slowly out from the shadows, reaching for me [**].

Because of this, the Nava-thalí all turned back to the way of Uthil Zuzas. And so, the Cosmic Power sent enemies to destroy Nin-vethí completely, allowing the Nava-thalí to return home at last. And that is what it did, but not before it saw fit to write the fate of Nin-vethí on the wall of the Palace of Unfading Majesty in incomprehensible bloody symbols. But before the Nava-thalí escaped, they visited Ev-thana, and got married there, as there were so many single women available, and so few eligible men. And so, the number of the faithful increased significantly. Thus they went around under the auspices of the Cosmic Power, using holy religious rituals to get rid of the clan of disgusting demons that had appeared everywhere, and then marrying the local folk. And as a result, the number of members in Ek-lesya Ev-thana grew tremendously, and they spread over all the Cruel Eyrth, creating Ek-lesya Vith-yahní, the World-Wide Church.

There’s screaming, howling, roaring, everything warping, ripping, breaking into smithereens. No sense, just terrible beating. The more I try to escape, the harder it is for me to breathe. I can’t move. The harder I try to concentrate, the less I can focus. Everything’s coming apart, and something, some parts of me, leave me, flying away on the heedless breeze, as some senseless yet strangely familiar blathering fills my mind —

The Archimandrites of the Temple would not tolerate the slightest disobedience, and those so foolish as to oppose them would pay the ultimate penalty, being executed, and put to death, by the sentence of Ek-lesya Vith-yahní, with water, and sword, and fire. But, it is written, there was one tribe who succeeded in escaping from them, so heinously cunning were they, eking an existence like beasts ceaselessly wandering the harsh desert, destitute and homeless. And, it is said, there they gave themselves over to frightful practices involving idol-worship, and rituals around an enormous cauldron of green brass, and worst of all, human sacrifice to false gods who visited them from a Harsh Planet revolving around the Dog Star in the Southern Reach. But because of their evil, their uncleanliness, and their sorcery, they were like invisible spirits amongst the yellow sand, the bare mountains, and the endless plains, and even the best assassins could not catch them to exterminate them. Some said that it was magic that they practised, and poison that they prepared, and devilish, extraterrestrial spirits that directed them. And the names of these alarming entities, so they said, were Las-ven, Kas-las, Nek-vas, Sak-sal, Ven-sak, Sal-kas, and Nev-las. Thus, as they continued to roam the wasteland beyond the bounds of civilization unchecked, amongst the legions of beetles and other hateful creatures, the unbelievers remained a harrowing thorn in the side of the Supreme Father-Church, even unto today. But whilst accepting that, every member of the World-wide Church rejoiced, reciting the immortal words of the Most Reverend Father Shaman-no – “Life is holy torture, suffering the inevitable fate of all, especially the great; one must accept the pain without complaint; it is a blessing to battle eternally against the oldest enemies.”

And there are the voices of those disgusting old beetles like chattering teeth,

“... dalatha, bravlu, klendru, eshempa – silpistí, madrolu, bamlaru, zileví – turikikihí, thirularop, bahuakah, veraza – endilda, andíshis, lilivalis, kestala – brubumbu, elentlova, kualuru, tithihenta – anvisashé, kouroakrí, ankelrerek, shezesista – vilizda, huiklé, vildarsí, delkurí,”

over and over. I hate them, and want to get rid of them once and for all, but I’m sure, too, they’re pestering me about something specific I should know, or remember, or understand. My attention wanders off like the Old Man of the Woods when I listen to them, and I spend days on the Nw Yrth in me mind while only half an hour has passed here on the Cruel Eyrth. I can’t stop remembering the Charm of Union from the joyful Green Zone over the sea, home to the Eyrwian khawví, and the golden spikni, and the leprechauns who weave rainbows – “I am you, and you are me; our own world shall be; where all will be free; live in glee then shall we.”

The earliest Archimandrites set to, performing their holy duties so zealously and sharing the uncompromising message of painful salvation through complete submission to the One True Church in the hope of dying undefiled and reuniting with the Cosmic Power. And as they did this, they had visions of the Ecclesiastical Splendour to come. And lo, there were spirits from the future, abbesses, high-priestesses, elders, cardinals, bishops, vicars, matriarchs, priests, popes, patriarchs, parsons, preachers, prelates, and prophetesses, processing in front of their lovingly violent eyes. And how greedily did those eyes feast upon the albs, the chasubles, the copes, the fantastic masks, the mitres, the white gloves, the jewelled rings, the multi-coloured coats, and on all the other symbols of the sacred offices. Then they were shown the sceptres, the armies, and the armoured vehicles, the palaces, the treasuries, the courts, and the fortresses, which they would have to create to spread and defend the marvellous message. They were filled with abject terror, and indescribable pride, and all-consuming zeal. And they swore that they would never give up the good fight until the very end of the Cruel Eyrth.

And then, Oh! Then my thoughts turn back to that Otherworldly Princess, Jelena, Helen, Elen, Eilidh, Helena, Aileen, Alyiona. Elena, the Fickle Moon is she – the gracious custodian, my sweetheart, my shadow, my strength, my trouble, my life, and the enchanting jailer too! I chase her all day and all night, but she always gets away from me {Loss}. Oooh, something very big’s gotta happen, sometime very soon. Or I’m goin’ to explode!

* * * * * * * *

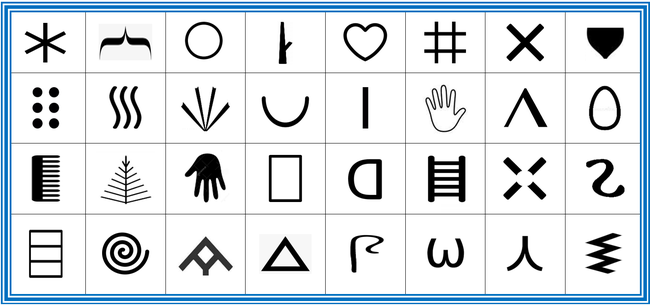

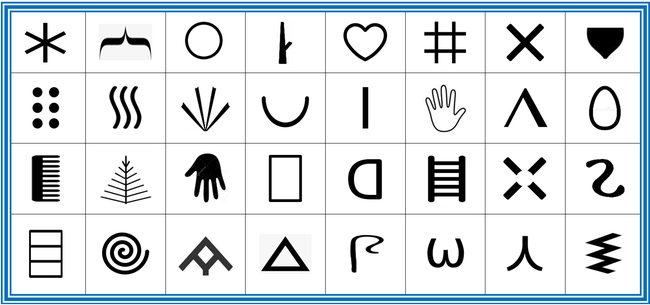

[*] No one has officially succeeded – as far as I know – in interpreting either the nature or the contents of this writing system, For sure, they have not published the results of their efforts if they have found any answers. But, after exhausting myself meditating, through dreary nights too many to count, delving into quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore, I discovered, despite how weak any weary I was, various tentative ideas regarding it. I imagine that the symbols are like those that follow.

In my mind’s eye I see glyphs dancing – aviform, circle, claviform, cordiform, hash, cruciform, cupule, dot, finger-fluting, flabelliform, semicircle, line, negative hand, open-angle, oval, pectiform, penniform, positive hand, quadrangle, reniform, scalariform, segmented cruciform, serpentiform, tectiform plan, spiral, tectiform sideview, triangle, unciform, w-shape, y-shape, and zigzag. Did they form a pictography or syllabary, an alphabet or an abjad? I’ll never know. But the pictures are doubtless full of power. And as everyone knows, the EGO’s sweated blood to create its own language to obfuscate, rule and dominate. Maybe my own research, despite how insignificant and unfinished it is, will function to strengthen the audience’s hearts and minds, and give them tools to resist and subvert the attacks by the ecclesiastical linguistic terrorists (and I’ve not even mentioned the slobbering statespersons here!). In terms of sound-enchantment, G.Ll. will have plenty to say about Hlothu’s Disks, Thuhlo’s Magic Squares, and glossolalia in due course. — P.M.

[**] I feel it will be educational to include the following narrative here. It is an episode called “Dark-Walking” from “Elaborations on Ensorcelling,” begun by the experimental enchanter Sikráks͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏ū Stévsū millennia ago and updated periodically by the most ground-breaking mages since then. — P.M.

In the harsh, tempestuous dusk, a deluge scourged the wasteland. The rebels kept nagging the Guerrilla Chief: Spin us a fable, Commando Chief. And the Chief went on as follows…

O night, O night, O night – O fateful night! Oh, I was not myself before, compared with what I am now. But there again, although I did not vocalize the ultimate invocation, I did play with it; let it slide through my thoughts, allow it to possess me. O, would I had never been born!

I had always delighted in eking out forgotten and forbidden lore to amuse myself, plague my enemies, and get hold of little things (and some not so insignificant ones, too) that I thought I needed or desired. After all, although I was but a lowly herbalist and self-taught naturalist, I was not, despite that, lacking in considerable innate talent in the way of enchanting, beguiling, and ensorcelling. (The folk said I was a hedge-witch, a wise-woman, an old doctor, and mistress of the elemental sap, for heaven’s sake!) But since my soulmate was kidnapped by the Bashr Owtlóh Hwdwmon’s despoilers (that shit-dog of a murderous tyrant!), I had been beyond all consolation. Not a single one of my potions would work anymore, either.

As a result, I had gone to live under the stars, like a vagabond without house or bed, wandering the World wherever my feet took me, and whither my heart demanded, in an effort to seek out my dearest lover and get him back, somehow or other. To be honest, I pretended to be a poetess on the sly, and garnered enough to live on by reciting sad, bawdy and comical verses to entertain the starving, pox-ridden serfs. As well as that, I succeeded in steering clear of the Bashr’s trample-troops who were going about everywhere pillaging and raping, burning and killing. Oh, how often I had implored the Chthonic Divinities and the Empyrean Spirits (illegally and in secret of course) to ensure that my dear Tewi was not slumbering in peace, but still living, and screaming, and inspiring free people to fight back wherever he was. Maybe I did not pray correctly: my voice crinkled like a dead leaf and my knees turned to gory gristle but there came never as much as a flea’s fart in answer.

So, I, Lenre Veka, travelled over the hills near the coal-tar pool smelling like the old, old days, and went past the last ever family of deer grazing amidst the brambles. I reached the World’s Backside to learn how the sapphire sea with its pods of whales changes at night-time to become a living being, its depths as purple as the blood of the mud-snake; and to be witness to the revenge of the forgotten corpses which have no goal but fulfilling their own inarticulate ends. I had brought an ultramarine exercise-book full of spells, a sack of flour, a tube of pins, a boot-jack, several whopping rubber-bands, a pint of vinegar, a pound of barley-sugar, a roll of wrapping-paper, and a small bone carved from a bigger bone, begged, borrowed or obtained else-wise here and there. I devoutly believed they would be of the utmost importance to me in my effective working, although i could not foresee how at the time. (Strange are the Witch’s ways, as they say!).

There, at sunset, the sky was ablaze, with a flock of playful flames, red and yellow, orange and pink – like poinsettias, dahlias, marigolds and petunias – tickling the clouds above the zesty water the hue of bayberry or myrtle, as the headland shimmered rudbeckia-gold. There, in the twilight’s splendid solitude, filled with the far-away laughter of hyenas, amongst the poisonous pink perennials, it was as if no-one on the Piteous Planet had ever known me. And there, I waited. Day gave way to night. A dark curtain bedraped the heavens’ countenance and comets scourged the sky as the stars hid their eyes. It began to pour with rain as darkness descended.

How had I come to be there in that particular alien spot, of all places under the Sun? Well, from the instant of my birth I had been an amateur hermetic logophilist. As a child, I had hoped to know; as a maiden, I had ached to develop; as a woman, I had decided to act. And that’s why I’d arrived at that totally out-of-the-way place. I’d persuaded myself at last to yield my will to the most primal demands of my innermost self. And there, the wet dunes glistened under the Moon like the Sorcerer’s silver plate, the waves glowing turquoise with the bioluminescence from the dinoflagellates. I knew that I had to acknowledge life as it truly is, eschewing fake orthodoxy, and embracing everything unethical, yucky, and evil as well as the lovely things, in order to win the most mystical and terrifying occult wisdom I had such an all-consuming desire to discover.

There stood I on the beach where the Horde of the Horsewomen of the Chestnut Stallions had used to come to burn their dead and spread their ashes, with the ancient rock of Vendl towering in the background, where the Minions of the Voice from Beyond spilled the pure blood of the living. And there I set out on the vapour-trail towards the spikni isle in the land of mists. In accordance with Propertius’ “Volume of Outlandish Words,” I set numberless focative mirrors to tempt taboo phantasms and enable me to notice things my eyes would never otherwise see. (I’d put the enchantments down on paper in italic hand in the blue book.) I adorned myself with beads like men’s eyes, tangerine lotuses, orang-utan skulls, and wyvern-ash. After this I offered in the manner of a practitioner of vrukhr-ía: “vathya” (a bottle of blood-wine), “vazí” (the skeleton of a fairy), “vasha” (a plate of fresh flesh), “vuthla” (grain harvested under a lunar eclipse), and “vaythna” (human seed poured out ritually), before calling on Those who Wait and Watch to come thither and open a door from the incredible to the possible:

Spirits of the Air: Conjure them!

Hobgoblins of the Urth: Summon them!

Imps of the Water: Call them!

Sprites of the Fire: Kindle them!

I’d convinced myself that the imperceptible entities could bring me anything if I were but to desire it keenly enough. And so, I hoped against hope to transform the exceedingly unprofitable prizes of the fantastic into a sumptuous feast I could gobble up to nourish myself for a very long time. The Moon’s evil eye was winking at me so ecstatically sadly and giving me unbelievable heebie-jeebies, but I plucked up enough courage to taunt myself, saying: “Ídw hey-Théybē, ídw kay hey-krawgéy” (that is, “Here is Thebe; dare you shout?”), as the Seven Wise Warriors had declared when they challenged Shaman-no. The face of the deep was like limpid ice, the water twinkling, reflecting the stars. Then, I kindled the incense made of mugwort and wormwood so that it smouldered on the embers in a huge bowl of copper and lapis-lazuli. After that I began to chant at the top of my lungs from “Lohsapí: The Tome of Grave-worms” (the chapter “Spectres of the Outer Spheres: Their behaviour and misbehaviour”). I was beating the ground rhythmically with the wand Mzraruk (which gives the might of ten practitioners to the Witch), and keeping time with the breaking of the waves, in order to summon the forbidden wraiths to appear.

We, the Urthkin, come from ash, we walk in ash, and unto ash we do return.

There is no release for a father’s daughter nor a mother’s son before life’s hot cord is severed.

O defenders of the walls of madness, accept these gifts and be silent!

May all the dead arise beyond the ivory door of lies, smell my burnt sacrifice, and remember!

Let all the forgotten souls come to me through the horny gate of truth and speak!

As my most earnest pleas rose towards the heights, the vault of the sky went pale like the aspect of an invalid on his death-bed. Then, there came over it a pink radiance, before the colour changed to be like a carnelian with crimson flames in its heart, and after that, like a great bruised gladiolus with its stamens aflame, the one straight after the other. Without warning, I was knocked flat on my back in the molten sand, burning, quivering, throwing out sparks, and unable to move a muscle or speak, as if I’d been struck by lightning. I’d reached the Land of Dom-danyel (in my mind at least), where the streets were paved with time, and lights came from everywhere as if through a layer of scum on top of a poisoned well.

And there, I went into the Lost Palace of Wth-randw with its bloody corridors, where a cruel wind was tearing at me with ice and frost as a dark fire screeched its song of silence without ever sharing a ragged kiss. Immediately, there came the beating of powerful wings. First, the Demoness Lámashaptan materialised, that is the Lady of the Seven Names. She had the body of a woman with long fingers and nails, covered in fur; the head of a lion with hair like snakes; a shark’s teeth, an ass’s ears, and a bird’s feet with claws like razors. She said: “Very many fools have summoned us incorrectly, and very few indeed have we rewarded according to their just deserts.” After that, there appeared amid a flare of emerald and scent of cinnamon, the Angel Aterateq (a word that means “the nameless one”) in the form of a flat star wrapped around with knotted threads of multicoloured illumination, rotating exceeding fast about a cruciform stake through its centre. He added: “Through us, the first are promoted, and the last are sent to oblivion,” whilst bobbing up and down like an ergot-crazed emmet.

“It is I who make quālitātēs occultae into themata probanda,” he said, “It is I who extinguish ratiō nātūrālis with lūmen grātiae,” she added [●]. And then, “It is we who bestow the gift of unexpected and torturous transformation according to our desire and the unspoken needs of the All-World,” said they, together. “Leave your aberrant species behind! Creation has come to fear the Urthkin more than Nature itself at last, because they learned to govern and utilize the fundamental forces to maim and destroy, making instrumental logic into an oppressive mythology.” I was still lying nailed to the spot on my back, mute and in enormous pain, looking up at the two goblins of perdition, completely flummoxed by their honeyed words.

They went on, coaxing: “A reassurance in dejection is having a comrade to partake of the woe. Come, join with us in the Love Abyss, dance, sing, be intimate, rid yourself of the joy of unknowing, melt, die, be reborn, experience our bliss, and go forth to do our will on the Urth.” And in that moment, I did not know whether I was being offered salvation or damnation. But I had no time at all to consider the sophological statements in detail. The two then began to caper about in the most coarsely provocative fashion, cursing the World’s children, and their children, and their children’s children until the end of time with the most tastelessly powerful imprecations. (I comprehended their meaning somehow without being able to understand the barbarous language itself.) And then – shameful to relate – they went at it, rutting rabidly like beasts of the field.

Before they reached the peak of their vile but hypnotic performance, the couple of un-Urthish entities exclaimed with one voice: “This is the sole occult mystery of existence. Listen, learn, and understand, therefore, so that you yourself shall possess the foundational secret of sorcery! After existence comes to be, it always exists with non-being, so that this non-being is combined in a simple unity with the being. Non-being contained in being; the fact that the graspable whole is in the form of being, unmediated: this is what constitutes determinateness as such. Accept our generous teaching before it is too late. Give yourself over to the sins of the flesh, share our visions, and become our child. For it is we who are the Fatal Mother and the Mute Father, living in the empty spaces beyond the starry spheres. It is we who bring forth the chaos which is source and ground of being. Take heed, poor mortal, and obey!”

I was but a weak woman at that time, although I’d steeped myself in magic words and encased myself in the mightiest charms. And whilst all these acrobatically sexual antics assaulted my senses, perverting my thoughts and causing me to feel so hellish wanton, they simultaneously made me feel quite nauseous. Unexpectedly, an image of my dear, lost Tewi came to appear before my overwhelmed mind like an angel of mercy and spirit of fortitude. And, as usual, he was singing one of his perplexingly babyish but very lovely lullabies: “Kake ziníno kukulo rímike lateví nutati kokiku lenova rímézé kítimoze vulako lamevu lítikéké” – “Weed and worm are word and thought; Cloud and spume are pain and care; Love, laughter and song: a sparkling life.”

This, thanks to all the powers, interrupted the abysmal scene threatening to tempt me to obliteration, for a second at least. As I vacillated, I lost forever the opportunity to submit to the exceedingly indecent and lascivious practices of the Corrupt Couple. In no time they united, struggling, groaning, and roaring like a moribund bull under the butcher’s knife, to form a clod of flesh, twitching and pulsating. Then, a beast burst out of this demonic womb, shaped like a dog with a pig’s head and a mule’s legs, hooves and tail. And it was also like a hurricane and a bonfire, like a waterfall of ice and a swarm of voracious locusts.

I was dazed and confused and at the same time I feared for my life, realizing that this was Tofthw-ba-Vwmno, the shaper of forms, the primal disorder whence everything came, and which will devour everything again at last. Time slowed down so that twenty-four hours felt like forty days and forty nights starving and hallucinating in the scorched desert. She spoke like this: “Your age is coming to an end. Your Planet is like a forgotten and forsaken island in the middle of the All-World’s enormous, empty ocean. There is no true beauty to be had without decay, and pure love is but manure. The sky is bruised, the weather rebels, the crops refuse to grow, the persistent rain has washed kingdoms and rulers away, and the dwelling-places have been ransacked by violent gangs. Soon, night will fall forever. So true are the words of our Holy Trinity. Your fate will be to be swept away by some tawdry disease like everything else, eventually. Believe me: we are completely right in our prognostications. Will you be the only one who refuses to yield to our irresistible temptation and so fails to purify your World, condemning it to a slow death, with no-one left to sing a threnody?”

I almost died then and there, but I managed to drum up courage and cry out the names of the Guardians of Every Quaternity: “Akantha-reya, Nokti-lẃca, Radyo-lárya, Numyu-líyteyz!” I don’t understand why, but it looked as if the tube containing the pins had exploded, allowing the tacks to shoot straight towards Tofthw-ba-Vwmno from below like hundreds of flaming needles, planting themselves in her rippling belly. (Maybe some unseen hand had chucked the tube using the boot-devil and elastic like a sling-shot.) Then, somehow, the brown paper was blown upwards, encasing the bounding she-creature and sticking tight to the spluttering form. (Perhaps some other unknown being had made strong gum from the sugar, vinegar and flower and then sneezed powerfully, I don’t know).

Tofthw-ba-Vwmno flew into a rage and flung herself down into the churning stew, creating a dizzying whirlpool and releasing a raging tempest as she pouted and whined: “The oppressors are those who are defended by the decrees but not bound by them; the downtrodden are those who are subject to the law but not protected by it. It would be better for you to learn and believe this without delay, then. Justice is a delusion, as only the despots create the rules. To break the cycle, it is necessary to annihilate the very concept of morality, and re-create it in an utterly new form. But you will not do this on your own initiative. Not without our patronage and favour.”

As the bride of chaos gibbered, cavorted and swore, making the salty soup churn, a massive ball of azure crystal appeared from the water before me to suck the light from the environment, and I was forced to stare at it. And there, in the absorbent globe, there was thick dark fog flying about in sickening spirals. I felt in my waters that the microcosmic sphere could collect any material and manipulate it to create and bring forth anything, and that if left unchecked it would spawn the most terrible abominations and spew them into our dimension. I would have to clear out the stinking sewers already starting to pour forth there by imagining and describing the finest things still existing in the real World (Oh, how cruel is Fate!), so that I could perceive them truly and clearly, and establish them inside it, if I were to have the slightest chance of surviving. And if I did not succeed, I was terrified that every particle of my essence would be ripped apart to feed the unremitting, harrowing processes of this pocket universe.

It was as if aeons were going by as I stood stock-still watching I-don’t-know-what happening, and during this period lacking time and space, my brain was free-wheeling. But in the end, I managed to get a grip on myself and began to order the dreams and visions and fashion things carefully enough in my mind. I saw then a lonely globule of black jelly hiding all atremble in the ocean’s deepest fissures and trenches. Although I could not understand it logically, I sensed that at its centre there was a vibrant kernel, an extraordinary seed, a minute living bone whittled from a massive dead one, and that some exceptional force would be essential for this unique phenomenon to sprout and develop. As soon as I’d thought this, lightning split the firmament in the ball with a quicksilver flash that struck the brine making the water shine blood-red. The shapeless jet bubble of organic matter shot up from the sludge in the long, narrow valleys, to the surface of the main, and floated off towards dry land.

To my great terror, I felt that the thing, whatever it was, was watching me intently because it was I who had caused it to exist; and that it was drawing meaning, energy and life from me. Without thinking, I began to recite instinctively the Seven Terrible Names, including the appropriate salutations, and (from where these came, I’ll never know, save for the fact that Tewi’s voice was guiding me), the diabolical phrases belonging to each one. And all the while, I was rocking back and forth like a petrified child.

The first one I gave voice to was: “Khaknunga – spreader of dreams, nightmares and visions –kakezinínoku!” The chunk of slime had expanded by then and looked like a substantial piece of flesh, throbbing so sorely. The thing struggled clumsily through the endless marshes towards the soaking forests, developing and growing bigger and bigger all the time. It was me who was enabling it, feeding it, giving it strength, and although I’d fathomed that I shouldn’t let the creature get too big, I couldn’t avoid it. I called out: “Mrangurmi – wielder of the material elements and the immaterial forces – kulorímikela!”

The bogey continued to change, develop and adapt before my stunned imagination. Soon, it had a body like molten rock under leathery skin, a voice of fire and cloud, and in its eyes, the bloodiest darkness. I called out: “Tsrawmnwa – essence of joy, reassurance, hope and peace – tevínutatiko!” It was faster and burlier than every other living creature; its senses were keener, its reflexes stronger, and its talons and fangs sharper than anything else. I cried: “Brgaldamatz – eye of the throne and master of the freezing fire – kikulenovarímézé!” Whilst watching it snarling like thunder before it became enraged and set fiercely upon everything around it, I saw that it was an outstanding creature; the embodiment of aggression, a bloodthirsty predator, and an insatiable carnivore. Indeed, it showed furious enmity towards its environment not just to survive, but for the sake of conquering, and slaughtering, and killing themselves. I could not be more astounded watching this thing that had arisen from my thoughts to develop beyond all imagining. I yelled (with the ethereal support of Tewi, perhaps): “Ksbilnw – keeper of the gate of the bottomless deeps – kítimozevula!”

Oh, how painful, then, did the image of my poor partner burn my mind, the syllables of his mournful song beguiling my ears: “Ka keziní noku ku lorími kela tevínu ta tiko kikuleno varí mézékí timo zevu lakola mevulí tiké ké” – “Youth’s bronzed banks beseech with trembling breath; Home’s cobalt waves coax with casual warmth; Night’s seductive silence splinters hankering hearts.” And thereupon, I lamented: “I want you now like a parched woman needs the cold water of a fountain in the desert. How much and how long have I desired to smell your hair and drown in your memory!”

I realized straight after that – Oh, horror of horrors! – that I had not managed to withstand and repel the Prodigious Parents, whilst stealing away their power. Instead, I had been absorbed in their disgusting, writhing substance. Had joined in with their most salacious coupling. Been flung into the Cauldron of Dissolution. And had been burned, dissolved, and refashioned in an utterly horrendous form. And worse than anything, the enchantments which were supposed to defend me had trapped me and bound me to them: as their child, their bondswoman, their toy, and their legate. I declared in my anguish: “Ksnandkanda – lord of mysteries, magic and rebirth – kolamevulítikéké!” Then – quaking, thundering, roaring, screeching coming from everywhere to fill air and water, soil and body, mind and spirit – for centuries or seconds, I know not – all followed by – nothing.

It was as if everything had ended in a devastating eruption, leaving nothing at all behind but excruciating treacly silence. I was hanging in the place of borders, vacillating between freezing and boiling, between being and nonbeing, partly alive having almost perished. Only a few cinders of reality still flitted about me there in the frontier-land, with the spirits of the former World stalking in the odour of the gunpowder, the brimstone, the hot metal and the burned flesh. Although I was filled with fright and revulsion, I found myself giving a name to the monster so that it could hear it, taste it, think it, possess it, crawl inside it, and so begin to exist on its own forevermore. Kuvukora – the night terror – was that name (Gvuvkhrw to the savages) – my child, my reflection, my fate. And the entity would be forebear to the race of creatures, the “nihilators,” that would go forth to possess the bodies and souls of the Urthkin, their hearts and their minds, terrorizing the World.

Little by little, but inevitably nonetheless, I began to lose my mind, bawling and baying, cursing, tearing my clothes, and pulling my hair out – I could not but do it. And then, there, I called upon the howling creature by its new name to come to me as I stepped through the outer surface of the cerulean ball. And – I would swear – I was forced to embrace the slobbering wild beast that smelled of death and was bellowing with a harsh, savage voice, hard and cold as stone, so that I could feel its strong heartbeat – and to draw it inside me, whispering that I was it, and it was I, and maybe thus had things always been. In a flood of rank despair, I let the words of the old oath of confession – “Síyluh! Fīat! Ékekon! Sódhlíytshé! Sow mowtit bí! Boyd veth’hlí! Ah-meyn!” – drop from my bleeding lips time after time until I swooned.

I came to my senses (after a fashion and in a manner of speaking), still overcome by this nightmarish situation. I was scorching hot and then as cold as slate, my whole body was afflicted: joints and stomach, head and muscles, marrow and sinews, eyes and teeth. Without knowing exactly what I was doing – I shudder to relate – I chose then to play a game with the Cowled Skeleton, clamouring the worst words without restraint: “Srkyulzuy – ruler of suffering, death and damnation, master of the Crevasse of the Condemned where children sacrifice themselves willingly to a flute’s elegiac tune – I am withholding the wondrous syllables; I shall not pronounce your magical word, although I know it only too well. Deliver me from this tribulation!” Every other option had evaporated.

I heard then a man-size pestle striking a stupendous mortar thrice, and saw roads cracking, towers toppling, castles exploding, and worship-houses burning. I had set in motion the end of the World on the day of judgement! And there was I, fighting frenziedly against myself; punching, kicking, biting, cutting, stabbing and scratching myself. It was as if I were prepared to do away with myself to cast the dread demon out from within me. At last (after forty years of torture, maybe, in that unreal kingdom of the imagination), in a gnat’s wink – wonder of wonders – there came – from nowhere – a smell, sour and fresh like acid to burn the fine hairs up my nose; white and violet flashing lights to blanket me and blind me; and childish giggling to give me goosebumps and send shivers down my spine. I passed out.

I awoke in front of an immeasurable entrance-way made of bone, skin and muscle. The calm sound of Tewi’s prattling had been transformed to be the most beautiful melody I’d ever heard: “Kakezi nínokuku lorí mikelate vínuta tiko kikuleno varímé zékíti mozevula kolame vulíti kéké” – “Stone and steel are defiant deeds; This righteous revolt a tumultuous tide; The valiant folk’s fortitude vanquishes foes!” I fell to my knees, bent over under the burden of my travails, beating my breast and wailing into the void as indigo-velvet as midnight that was expanding all around me like a suffocating counterpane to drown me in a river of perpetual nothingness. But even then, outside the mute gates of Heli-hrelí, the Harvester of Lives, Hthohla, would not descend from his blood-stained eyrie to gather me in.

With the aid of some unknown power, I had indeed been condemned to live. There, before the Doors of Vendl, I came to know and celebrate that I myself had experienced things that no eye had tasted, no ear spoken, no nose seen, no hand heard, no tongue felt, nor any heart smelled ever before. I had accepted that one’s experience yields common-or-garden knowledge, but that revelation is imagination’s gift, and that there is a specific yet unforeseeable and very high price to every true dream too. That is why the sweetheart, the poetess and the madwoman are so alike (and I had been all three of these). They understand that story and fantasy are not mockeries of truth but the substance of a new reality which will persist when certainties have rotted away. And they have learned not to trust the tale-teller, only the living yarn itself.

I came to the indubitable conclusion on the spot, too, that half blessed spirit are even the very best of us, the Urthkin, and half warlike ape. It’s only love’s frail anthems that bring a candle to heal the wounds of both parts to some degree at least, and only the fragile cement of what remains of society that prevents our kind from annihilating the World and ourselves at one and the same time. But since the feral wolves are intent on ravaging, despoiling and destroying, we, the meek lambs must force ourselves to grow fangs and horns and talons, and fight back mercilessly.

My friends, I saw that I had come into my life soft and weak, buffeted through space and time. And that then I’d turned into a beautiful lapwing, plunging into events as if they were whirlpools in the torrent of causality. But by now, comrades, I’ve developed to be strong and decisive, owning that it’s necessary for someone brave and unyielding to regulate processes and drive developments if existence is not to fall into utter chaos. And, as a result of everything I have experienced, accepted from the bottom of my heart, and revealed to you here, today, I’ve hardened the shattered cardiac organ in my chest (or maybe it did that by itself), and steeled myself for the bloody war to come.

I declare, therefore, that Grundr Vwtshr shall henceforth be my name. I swear, too, that I am convinced, in the depths of my bowels, that it is only I who can take the fight to the inhuman enemies, to the despicable armies of the Bashr Owtlóh Hwdwmon – without becoming as bad as him, or worse – and prevail. And so, onwards to victory shall I lead you! ALL POWER TO THE RIGHTEOUS REBELS! OBLIVION FOR THE OPPROBRIOUS OLIGARCHY! EXTINCTION FOR THE EXECRABLE EPARCHS!

* * * * * *

[P.M.] And so, the rain-soaked public peroration – impassioned indeed, but also tremulous, under the bravado – wound to its rabble-rousing conclusion. But, in truth (I have sensed whilst scrying in the vile cauldron), Grundr Vwtshr’s heart was fluttering, her conscience prickling, and her face burning with guilt and shame, as she cogitated forlornly as follows.

“Oh, such noble words! And yet, it was me who’d freed the fiend from the phial so to speak, releasing Movukala (known as Mvukhla by the barbarians) – the one who walks in the darkness – my sister, my look-alike, my end – on the World. And I know that I’ll have to fight tooth and nail every second of every day to stop myself becoming a debased brute who’s the embodiment of the Old Ones, working to fulfil their heinous desires on the Urth, even though I do now indeed possess outstanding strength in body and mind.

“Here I am, then, with the first words of the freedom-fighters’ brand-new shaggy-dog-story boiling in my mind: ‘NOW, EACH NIGHT IS SO STORMY AND DARK; AND IT’S ALWAYS POURING DOWN BUCKETS. THE REBELS SAY TO THE BRIGAND CHIEF: GIVE US A STORY, MOST DARING OF CHIEFS. AND THE CHIEF BEGINS HER STORY…’. It’s torture to me. Oh, if only I could constrain and command the cacodemon caterwauling inside me – my lover, my death – my self!”

[●] The Etruscan phrases quoted here mean: “occult qualities” and “obvious propositions,” and “natural reason” and “the light of grace.” The “nihilators” are formally called “nihilālēs.”

Hanesion Hynod 13 Sylweddoli

O: Hanes Diderfyn yr Eglwys Fyd-Eang Gysegr-lân

Fyddai Uthil Zuzas ddim yn gadael i Rev-zilé adael, gan ei gwahodd i ymrithio tu mewn i sffêr o gornblith ddu a’i lapiodd wedyn mewn haen denau o arian fel na allai hi ddianc. Ac yno arhosai hi’n rhefru a rhuo, wrth fradychu llawer iawn o eiriau cyfrin, cyn iddi rannu cyfrinach ysgrifennu gyda fe. A dyna a wnaeth hi o’r diwedd, ond yn anfodlon, ac wrth felltithio’i geiriau wrth iddi’u dweud nhw, yn hollol groes i’w datguddiad wrth Nilroth o’r goeden bomgranad yn llosgi. Roedd Uthil Zuzas yn mynnu cael y teclyn hwn i hybu datblygiad cymdeithas ac ehangu’i ddylanwad. Gwelai y gallai greu cofnod parhaol o’i fawredd, ei gyfreithiau, ei athrawiaeth, a’i drefn gymdeithasol berffaith i genedlaethau i ddod, hyd yn oed pan fyddai cof y werin wedi crebachu i ddim. Byddai dogfennau wedi’u creu ganddo yntau, yn cynnwys symbolau sacredig sefydlog, a llythrennau cryfion, yn well o lawer na chofnod llafar, mympwyol, fyddai bob amser yn newid a marw fel creadur byw. Gydag ysgrifennu, fe fyddai’n torri llwybr o’r gors bygddu wedi’i chreu gan nerth swynol y tafod, oedd yn rheibio gwrandawyr ag addewid dirnadaeth gyntefig, ond wedyn yn eu twyllo a drysu eu meddyliau pitw. Ac felly Uza-ma-Dauth fyddai’i enw. Efe fyddai biau Iaith y Nef, ac efe fyddai’n ei rheoli a’i gorchymyn, a’i defnyddio, yn ei phurdeb dilychwin a digyfnewid.

O: Cariad, Colled, Chwilod

Ac er do’n i’m yn moyn ei neud, roedd yn rhaid i fi syllu arni hi. Fe weles i wedyn taw ei hwyneb hi oedd wyneb cyfarwydd ‘yn Mam druan, ro’n i’n charu gymaint nes iddi fynd; a hyd yn oed fwy, wedyn. Y foment ‘na, ro’n i’n teimlo mor unig, mor llawn hiraeth, oedd y delweddau o ‘nghwmpas mor drwchus a rhyfedd, a thorrodd ‘nghalon. Ond cyn gynted â nes i amgyffred pwy oedd yno o ‘mlaen i, es i i wylltio o weld nad wyneb gwelw menyw sâl yn marw o glefydd nychu oedd yno, ond yn gynta wedd tywysoges brydferth tu hwnt ac ar ei gwefusau perffaith finlliw du, ac wedyn delwedd hen wraig dra urddasol a llym yn iwnifform waedlyd nyrs. Ro’n i di dychryn trwo i o sylweddoli taw yng ngŵydd y Dduwies Driphlyg ei hunan o’n i. Ac wedyn – a bron i ‘nghalon stopio – ymddangosodd ‘yn wyneb i’n hunan, yn llawn ofn, a llid – a chasineb. Gyda’r gair, a’r wawr yn dechrau torri, fe ges i ‘nghipio ymhell y tu uchaf i’r gorthwr.

Fe’i gwelai’i hun fel technolegwr yn adeiladu peiriant eglurhaol, perffaith, fyddai’n dilyn glasbrint sobr a haniaethol y testun i oresgyn methiannau parabl naturiol. Efe a ddeuai’n Rhiant i’r Genedl; sefydlwr traddodiad sanctaidd; ffynhonnell, lledaenwr, a chyflafareddwr gwirionedd; a chynhaliwr grym y wladwriaeth drwy’r milenia. Efe fyddai’n torri’r cysylltiad rhwng awdurdod gormesol y teulu biolegol dirywiedig a rhwymedigaeth daeog y plant, a rhwygo’r gadwyn yn rhwymo anrhydedd anhaeddiannol y meistr ac ymroddiad dall y disgybl. Ymhellach, fe ffurfiai arysgrifau parhaol gysylltiad agos iawn rhwng y rhai byw a’r rhai marw, rhwng sicrwydd y gorffennol a phosibiliadau’r dyfodol. Dechreuon nhw felly adeiladu Tai Aileni a’u llenwi nhw â’r glyffiau glân, rhyfedd a nerthol, ro’n nhw’n eu caru a’u hofni ar yr un pryd.

A dyna o’n i’n estyn ‘mreichiau i ormesu’r Ddaear Greulon, wrth i edau o dywyllwch a golau darddi o ‘nghorff i ‘nghysylltu â phawb a phopeth yn y Ddau Fyd, fel cortyn bogail yn cysylltu mam a babi. Ac Www, roedd yn deimlad mor wych! Ro’n i wedi neidio i’r gwacter, gan obeithio cael ‘nileu, ond yn lle ‘ny wedi cael ‘yn achub, neu’n arbed – ond i ba bwrpas yn enwedig? Agorodd sgwâr hollol ddu o ‘mlaen i wedyn, ac o’i amgylch ar fynyddoedd emrallt, gimerâu’n cynnwys blaidd gwaetgoch, llewod piws, teigrod indigo a draig wen yn llosgi popeth â fflamau melys.

Ond daeth yr ysgrifennu’n fagl a hunllef i Uza-ma-Dauth, am iddo ddod i gredu o’r diwedd fod ei syniadau’n hollol ddi-werth os nad o’n nhw wedi’u hysgrifennu, a’u darlledu, a’u darllen gan eraill, ac yn wir gan yr holl Ddaear Greulon. Ac wrth iddo sgriblan fwyfwy, ac wrth i fwy o bobl lyncu’r geiriau heb fod yr awdur yno i reoli’r broses ac atal darlleniad anghywir, fe ddechreuon nhw, yn ôl eu harfer, ynganu’r geiriau â’u goslef unigryw eu hunain, a’u newid nhw, ac yn waeth, fe ddalion nhw ati i ddadansoddi drostyn nhw’u hunain. Ac wedyn, heb awdurdod y meistr, fe ddyfeisien nhw ddehongliadau cwbl groes, a gadael iddyn nhwythau weld ystyron awgrymiadol, sathredig, a chyfareddol yn y testunau, a chreu hanesion ffansïol ganddyn nhw.

Arnofiwn i wedyn am hydoedd, mae’n ymddangos, gan hwylio dros yr Holl Fyd ar wely hedegog. Wrth chwilio yn yr Hyd Deheuol, ger Seren y Ci, am wybodaeth guddiedig ynghylch diddymu ofn a gorchymyn cariad, ro’n i’n meddwl, “Peidiwch byth â’m deffro o’r cwsg hwn. Ond byddwch yn sicr, fel rwy wedi rhodio llwybr y sêr dan fyfyrio, felly dw i hefyd wedi bod yn beichio llefain.” Falle i fi gyrraedd Muze-mara ar hap, gan ymweld â pholyhedron amryffurf, dirfawr Ví-aza. Ble bynnag ro’n i, fe ddes i o hyd i ryw injan difodi organig, neu ryw beiriant trawsffurfio. Am nad o’n i’n gwbod beth o’n i’n neud, ges i ‘nghyfareddu ganddo, a nes i’i alw i lawr i orwedd fel chwistrell yn sownd yng nghnawd y Byd o gaethydd. Er bod finnau a naeth hyn, o ble roedd wedi dod, neu hyd yn oed beth oedd e mewn gwirionedd, yw dirgelwch llwyr o hyd. Ond rywbryd pan fyddwch chi’n agor drysau, bydd pethau annisgwyl nad oes eu heisiau yn dod drwyddo, fe ddysges i ar ‘nhraul ‘yn hun.

Ac wrth i bobl eraill glywed y straeon yn eu tro, fe ddechreuon nhw gasglu ystyron ar hap i neud synnwyr o’r deunyddiau’n bodoli’n barod. O’r araith gyhoeddus, daeth mytholeg, ac o hon tyfodd ideoleg, a’r naill garfan yn defnyddio’r geiriau fel sail ac esgus i fychanu, niweidio, neu ddifodi’r llall. Daeth y gair ysgrifenedig, oedd i fod yn wreiddiol yn ffynhonnell cyfraith, cronfa meddyginiaeth, a moddion iachawdwriaeth, hefyd yn felltith, gwenwyn, a buwch ddihangol i fynych abredau. Ac felly hefyd fe gafodd hudoliaeth ei eni, yn anghenfil bach, mud, heb rywogaeth na ffurf benodol, ond yn frawychus yn enwedig o achos ei gallu i gyflawni pob diben yn ddiedifar. A gwae nhw! Gweithred gyntaf y drefn newydd oedd gwyrdroi cyfiawnder. Wele’r Famfaeth Ryfelgar o’r hen chwedl a laddodd ei gŵr y Meimiwr Milain trwy ddweud jôcs wrtho nes iddo chwerthin i farwolaeth. Ac wedyn fe gafodd ei hamddiffyn gan y Clown Bwrlésg o'r Syrcas Absẃrd a ddefnyddiai ryddid y masg a’r colur i jyglo ag iaith, gan ddarbwyllo’r llys nad oedd yn bosib i ddyn yn ei iawn bwyll gredu mai geiriau allai niweidio neb. Ac felly fe gafodd hithau’i rhyddfarnu’n euog o bob cyhuddiad, ac aeth yn ei blaen i lofruddio’r Brenin, ac wedyn, flynyddoedd maith yn ddiweddarach, i wneud difrod ar y Ddaear Greulon oll.

Ac ro’n i wedi’i wysio, a’i danio, neu’i ddeffro, nes iddo amlygu’i hun ac arllwys ei suddion treulio ma’s i fwydo ar y Byd, neu’i fwytho fe, falle, yn ôl ei arfer ei hun. Fel sgrin sgrio byw, roedd wedi gwatwarus ddechrau sugno i mewn be bynnag safai mor addfwyn o’i flaen, ac ymdebygu iddo, a’i ddynwared gan ddefnyddio’r deunyddiau crai o’i gwmpas. Sut, neu pam, mae’n gweithredu i gyflawni’i nodau, a beth yw’r rhain, fydda innau fyth yn dyfalu. Mae fel parasit yn ffurfio symbiosis mor berffaith â’r Blaned Letyol fel mae'n uno’n llwyr â fe, gan chwarae gêm ddychrynllyd wrth falu a gwyrdroi popeth mae’n ei greu yn ei Fyd Newydd, Braf.

Ac wele! Dyma beth fydd yn digwydd o fynd ar gyfeiliorn oddi ar lwybr daioni, uniongred. Yn raddol, dros y milenia, diflasai llwyth Nava-thalí ar ymneilltuo o weddill y Ddaear Greulon, perfformio’r defodau, a chadw’r gannwyll gysegredig yn llosgi yn Nhŷ Aileni yn y sigwrat enfawr yng nghalon y ddinas. A gwae nhw! Bu i aelodau un cast wneud gwaith oedd yn gymwys i aelodau cast arall, gan eu halogi’u hunain’n ddybryd. A chyda’r fflam lân yn crynu a diffodd am y tro cyntaf mewn canrifoedd o achos anffyddlondeb y Nava-thalí, fe falodd rhengoedd Teyrn Nin-vethí waliau’u dinas, a’u cipio ymaith i Aliz-íya. Ac yno, y Del-hurí oedd enw’r brodorion ar yr alltudion. Ac ro’n nhw’n dioddef yn enbyd dan wylo, ac ubain, a rhincian eu dannedd, pan nad o’n nhw’n gweithio hyd at yr asgwrn yn y pyllau halen oedd bron yn ddiwaelod, ac yn andros o boeth.

A finnau’n dal dan ddylanwad meddwol y cyffur a heb sylweddoli’n wir beth o’n i’n neud, fe sgrifennes i lythyr at bwy bynnag fyddai’n dod o hyd iddo yn y dyfodol, yn cynnwys ‘yn syniadau ac esbonio beth oedd yn ‘ngyrru i ‘mlaen. Pan ddes i at ‘nghoed yn nes ‘mlaen, a dod yn ôl i Byrth-y-Fall, fe guddies i fe yn rhywle heb ei ddarllen. Ro’n i’n teimlo’u bod nhw’n chwerthin am ‘mhen i o hyd, rywsut, yr Hen Dduwiau Arallfydol, o ‘ngweld i’n dal i fyw, ond mewn poen ddirfawr drwy’r amser o achos y briwiau. Gweles i wedyn do’n i’m wedi marw yn y lle cynta, ac felly, wel … Ro’n nhw’n greulon dros ben, ac yn gwneud troeon gwael â fi. Neu, falle, doedd dim taten o ots da nhw. Ond yn wir, un peth wyddwn i –doedd a nelo ‘ngheisiadau cloff i ar fwrw hud ddim byd o gwbl â’r cawlach llwyr ‘ma.

Ac yno dim ond un ohonyn nhw o’r enw Tho-vítha o lwyth y Nava-thalí a gadwai gyfraith Uthil Zuzas yn ei gwir ffurf, er gwaethaf gorchymyn Meistri’r Ddinas, gan gipio celanedd yr alltudion a’u hydoddi mewn asid sanctaidd. Pan fu farw ei wraig ar ôl bwyta un hedyn o bomgranad rhyfedd o flasus a ddygodd o ardd y Dywysoges, naeth Tho-víthah ei hamlosgi ar ben tŵr agored, gan adrodd, “Wele Ferch Dolur wedi’i thaflu i’r tân yn llaw Buddugoliaeth yng ngwlad gas Aliz-íya. Fe fyn y gyfraith fod rhaid i ddyn roi’r meirwon yn y pridd mall ble maen nhw’n cwympo. Ond ni chaiff yr aderyn dieithr hwn, coron gwerin Thali-Himila, fyth ei ddaearu, ond fe fydd yn dianc eto fel arfer.” Doedd y Meistri ddim yn falch o glywed hyn o gwbl, a chyhuddon nhw Tho-vítha o’i lladd. Fel cosb, fe gafodd ei ddallu gan haid o golomennod duon a brain gwynion, a rwygodd ei lygaid allan wrth iddo weddïo am achubiaeth, cyn iddo gael ei allyrru o Nin-vethí i farw yn yr anialdir mawr, coch y tu hwnt i’r muriau.

Felly, mae’n wir flin da fi, dw i’n gwbod taw anorffenedig ac anfanwl yw’r holl ddyfaliad ‘ma. Ond er gwaetha’r diffygion oll, gobeithio dyw e’m yn ddiffrwyth, myn y Delw-addolwyr Dioglyd! Wedi dweud ‘ny, dyw ‘nheclynnau hud ddim yn gweithio rhagor, mae’n swynganeuon wedi torri, a does ‘run ateb go iawn ‘da fi, a dyna achos dw i’m yn gallu ‘ngorfodi fy hunan i ofyn y cwestiynau hagr. Mae fel petai drws o ‘mlaen i, yn gilagored, a llawer o drysor ansbaradigaethus tu draw iddo, ond hefyd rhyw sŵn uchel fel anifeiliaid gwyllt yn y düwch tu fewn.

Yno, yn yr anialdir mawr, coch, ymddangosodd y Pŵer Cosmig i Tho-vítha ar ffurf Rev-zilé. Pe buasai wedi gallu defnyddio’i lygaid, fe fyddai wedi gweld bod hithau’n sefyll ar y Lloer Gilgant gyda haid o bilipalod cochion yn chwim droi’n adar bychain yn hedfan o’i chwmpas, a chylch o sêr am ei phen. Roedd hi’n datod clymau mewn rhuban hir, porffor, a’i thraed yn sathru ar sarff wedi torchi oddi dani, a madfall fawr, felen, hefyd. Dywedodd Rev-zilé wrtho: “Mae cwlwm anghred wedi’i ryddhau gan ufudd-dod eich ffydd hyd yn oed mewn gwlad estron. Ewch gyda fi i Ev-thana, ble mae cythraul o’r enw Az-mothus yn lladd yr holl briodfeibion ar noson y briodas!” Fe gytunodd Tho-vítha oblegid nid oedd ganddo ddewis arall. Ac ar eu ffordd yno dwedodd Rev-zilé wrtho am ddal pysgodyn, a’i goginio. Fe wnaeth Tho-vítha hynny, a chyda chymorth Rev-zilé, fe ddarganfu fod bustl berwedig y pysgod yn gwella dellni, ac y byddai past yn cynnwys y galon a’r iau’n bwrw allan gythreuliaid.

Dw i angen craffu ar beth bynnag sy yno ymhlith y budreddi a’r drewdod, ond dw i’m yn ddigon cryf, ac yn camu’n ôl yn dawel, gan gau’r drws a sleifio bant. Dw i’n brawychu achos bod popeth mor wallgo a disynnwyr, a dw i’n gwbod does dim ffordd o ennill gêm os dych chi’n chwarae heb bac llawn o gardiau. Ond dyma fi’n gweiddi o galon dyw’r pethau’n ‘ngyrru i ‘mlaen ddim yn hunanol, ac fe fydda i’n dal ati i drio newid y Ddaear Greulon gyda’r partïon, a’r gerddoriaeth, a’r Neges Fawr, ac o ganlyniad dw i’m yn digalonni ‘to.

Fe iachaodd Tho-vítha ei hun o’r dallineb, ac aeth i Ev-thana i fwrw’r cythraul allan. Fe fedrai weld wedyn, er nad oedd ganddo lygaid yn ei ben. Pan gyrhaeddon nhw Ev-thana, fe wnaeth Tho-vítha hynny. Ac wedyn, briododd e Ze-ríya, un o’r priodferched oedd wedi colli’i chariad, ac ymgartrefu yno, ar ben mynydd o’r enw Ek-lesya, a dod yn gyfoethog dros ben, trwy werthu ffisig parod o bob math a wnâi gyda chefnogaeth Rev-zilé. A hwythau’n datgan eu gweithredoedd da, ac addoli, a rhoi clod, ac ymprydio a rhoi elusen yn unol â dysgedigaeth Uthil Zuzas, fe ddaeth y tŷ moethus ar ben y mynydd yn gysegr ac wedyn yn deml. Ac ar ôl hynny, Ek-lesya fyddai’r enw ar bob teml, cysegr, a thŷ addoli. Ac fe aeth neges yn ôl i’r alltudion yn Nin-vethí yn Aliz-íya o ganlyniad i hynny.

Ond, bob nos, mae’r bwystfil gwallgo sy’n moyn ‘yn meddiannu’n rhoi gwybod i fi ei fod yn teyrnasu o hyd dros Fro’r Brwyn. Dyma’r Rhodiwr mewn Tywyllwch a rhag ei wep ffodd daear a nef amser maith yn ôl. Mae’i fysedd yn eithriadol o hir. Mae’n neud sŵn byrlymu, tagu, udo, fel ‘sai’i holl ysgithrau rif y gwenith yn cael eu tynnu o’r deintgig yn y fan a'r lle. Mae’r llygaid coch heb unrhyw gwyn ynddyn nhw’n sgleinio, yn llawn gwaed. Mae’n lledu’i aelodau’n ara ara ma’s o’r cysgodion, gan estyn amdana i [**].

Oblegid hyn, fe drodd y Nava-thalí oll yn ôl at ffordd Uthil Zuzas. Ac felly fe anfonodd y Pŵer Cosmig elynion i ddinistrio Nin-vethí yn llwyr, gan adael i’r Nava-thalí ddychwelyd adref o’r diwedd. A dyna a wnaeth, ond nid cyn iddo weld yn dda ysgrifennu ffawd Nin-vethí ar wal Palas Mawredd Anniflan mewn symbolau annealladwy o waed. Ond cyn i’r Nava-thalí ddianc, fe ymwelon nhw ag Ev-thana, a phriodi yno, gan fod cynifer o fenywod sengl ar gael, a chyn lleied o ddynion priodadwy. Ac felly gwnaeth nifer y ffyddloniaid gynyddu’n sylweddol. A dyna lle’r o’n nhw yn mynd o gwmpas dan nawdd y Pŵer Cosmig, gan ddefnyddio defodau crefyddol glân i gael gwared ar y llwyth o gythreuliaid ffiaidd a ymddangosasai ym mhob man, ac wedyn priodi’r werin leol. Ac felly y tyfodd y nifer o aelodau yn Ek-lesya Ev-thana yn aruthrol, ac ymledon nhw dros y Ddaear Greulon oll, gan greu Ek-lesya Vith-yahní, yr Eglwys Fyd-Eang.

Dyna sgrechian, udo, rhuo, popeth yn warpio, yn rhwygo, yn torri’n deilchion. Sdim synnwyr, dim ond curo ofnadw. Mwya’n y byd mod i’n trio dianc, anodda’n y byd ydy i fi anadlu. Dw i’m yn gallu symud. Mwya’n y byd mod i’n trio canolbwyntio, lleia’n y byd mod i’n gallu ffocysu. Mae popeth yn dod oddi wrth ei gilydd, a rhywbeth, rhai rhannau ohona i, yn ‘y ngadael i, gan hedfan bant ar yr awel ddihidio, wrth i ryw faldorddi dissynnwyr ond rhyfeddol o gyfarwydd lenwi’n meddwl i —

Ni oddefai Archimandriaid y Deml y mynmryn lleiaf o anufudd-dod, ac fe fyddai’r rhai hynny mor ffôl ag i’w herio nhw’n talu’r gosb eithaf, gan gael eu dienyddio, a’u rhoi i farwolaeth drwy ddedfryd Ek-lesya Vith-yahní â dŵr, a chleddyf, a thân. Ond, ysgrifennir, roedd un llwyth a lwyddodd i ddianc rhagddyn nhw gan mor anfad o gyfrwys o’n nhw, gan grafu byw fel bwystfilod yn crwydro’n amddifad a digartref yn yr anialdir llwm. A, meddir, fe fydden nhw’n ymroi i arferiadau dychrynllyd yn golygu delw-addoliaeth, a defodau o gwmpas crochan enfawr o bres gwyrdd, ac yn waethaf oll, aberth dynol i au dduwiau a ymunai â nhw o Blaned Yrth yn troi o gwmpas Seren y Ci yn yr Hyd Deheuol. Oherwydd eu drygioni, a’u bryntni, a’u swyngyfaredd, ro’n nhw fel ysbrydion anweledig ymhlith y tywod melyn, y mynyddoedd llwm, a’r gwastatiroedd diderfyn, ac ni fedrai hyd yn oed yr asasiniaid gorau eu dal nhw i’w difodi. Fe fyddai rhai’n dweud taw hud a ymarferen nhw, a gwenwyn a baratoen nhw, ac ysbrydion allfydol, dieflig a’u cyfarwydden nhw. Ac yr enwau ar yr endidau brawychus hyn, medden nhw, oedd Las-ven, Kas-las, Nek-vas, Sak-sal, Ven-sak, Sal-kas, a Nev-las. Felly wrth iddyn nhw ddal i rodio’r gorest y tu hwnt i ffiniau gwareiddiad heb lestair, ymhlith y llengoedd o chwilod a chreaduriaid atgas eraill, parhâi’r anghredinwyr yn ddraenen ingol yn ystlys y Dad-Eglwys Oruchaf, hyd at y dydd heddiw. Ond wrth dderbyn hyn, gorfoleddai pob aelod o’r Eglwys Fyd-Eang, gan adrodd geiriau anfarwol y Parchedicaf Dad Shaman-no – “Artaith lân bywyd, ffawd anochel pawb dioddef, yn enwedig y mawrion; rhaid i ddyn dderbyn y boen heb gŵyn; bendith brwydro’n dragwyddol yn erbyn y gelynion hynaf.”

A dyna leisiau’r hen chwilod ffiaidd ‘na’n fel rhincian dannedd, yn dweud,

“... dalatha, bravlu, klendru, eshempa – silpistí, madrolu, bamlaru, zileví – turikikihí, thirularop, bahuakah, veraza – endilda, andíshis, lilivalis, kestala – brubumbu, elentlova, kualuru, tithihenta – anvisashé, kouroakrí, ankelrerek, shezesista – vilizda, huiklé, vildarsí, delkurí,”

drosodd a throsodd. Dw i’n eu casáu nhw, ac yn moyn eu difa’n llwyr, ond dw i’n siŵr hefyd fod nhw’n ‘mhlagio i am rywbeth penodol ddylen i wbod, neu gofio, neu ddeall. Dw i’n llesmeirio fel Hen Ŵr y Coed wrth wrando arnyn nhw, ac yn hala dyddiau ar y Nw Yrth yn ‘yn meddwl tra bydd dim ond hanner awr wedi pasio yma ar y Ddaear Greulon. Dw i’m yn gallu peidio cofio Swyn Uno o’r Parth Gwyrdd llawen dros y môr, yn gartre i’r coffi Eirwig, a’r spikni aur, a’r coblynnod sy’n gwau enfysion – “Y ti dw i, ac y fi wyt ti; ein byd ein hun fydd; ble pawb fydd yn rhydd; byw’n hoenus wnawn ni.”

Aeth yr Archimandriaid cyntaf ati i berfformio’u dyletswyddau glân mor selog a rhannu’r neges ddigyfaddawd o waredigaeth boenus trwy ymostyngiad llwyr i’r Un Wir Eglwys yn y gobaith o drengu’n bur ac aduno a’r Pŵer Cosmig. Ac wrth iddyn nhw wneud hyn, fe gawson nhw weledigaethau o’r Ysblander Eglwysig i ddod. A dyna lle’r oedd ysbrydion o’r dyfodol, yn abadesau, arch offeiriadesau, blaenoriaid, cardinaliaid, esgobion, ficeriaid, matriarchiaid, offeiriaid, pabau, patriarchiaid, personau, pregethwyr, preladiaid, a phroffwydesau, yn gorymdeithio o flaen eu llygaid cariadus o dreisgar. Ac mor farus y gwleddai’r llygaid hynny ar yr albau, y casulau, y cobau, y masgiau ffantastig, y meitrau, y menig gwynion, y modrwyau gemog, y siacedi brithion, ac ar holl symbolau eraill y swyddogaethau sanctaidd. Wedyn fe ddangosid iddyn nhw y teyrnwiail, y byddinoedd, a’r cerbydau arfog, y palasau, y trysorfeydd, y llysoedd, a’r amddiffynfeydd, y byddai’n rhaid iddyn nhw eu creu i ledaenu ac amddiffyn y neges fendigedig. Fe gawson nhw eu llenwi ag arswyd llwyr, a balchder annisgrifiadwy, ac aidd hollysol. Ac fe dyngon nhw na fydden nhw byth yn rhoi’r gorau i’r frwydr dda hyd at ddiwedd olaf y Ddaear Greulon.

Ac wedyn, O! Dyna’n meddyliau’n troi’n ôl at y Dywysoges Arallfydol ‘na, Jelena, Helen, Elen, Eilidh, Helena, Aileen, Alyiona. Elena, y Lleuad Oriog yw hi – y warchodwraig radlon, ‘y nghariad, ‘y nghysgod, ‘y nghryfder, ‘y ngofid, ‘y mywyd, a cheidwad cyfareddol y carchar ‘fyd! Dw i’n ei hymlid hi drwy’r dydd a gyda’r nos, ond mae hithau bob tro’n dianc rhagddo i. Www, rhaid i rywbeth mawr iawn ddigwydd, rywbryd yn fuan iawn. Neu dw i’n mynd i ffrwydro!

* * * * * * * *

[*] Does neb wedi llwyddo’n swyddogol – am wn i – i ddehongli na natur na chynnwys y system ysgrifennu hon. I sicrwydd nad ydyn nhw ddim wedi cyhoeddi canlyniadau’u hymdrechion os dod o hyd i atebion a naethon nhw. Ond, ar ôl fy lladd fy hunan yn myfyrio, drwy nosweithiau syrffedus yn rhy niferus i’w cyfri, wrth dyrchu i gyfrolau henaidd a rhyfedd yn llawn llên anghofiedig, nes i ddarganfod, er mor wan a lluddedig o’n i, sawl syniad petrus yn ei chylch. Dw i’n dychmygu bod y symbolau fel y rhai a ganlyn.

Yn llygaid fy meddwl dw i’n gweld glyffiau’n dawnsio, yn cyfateb i: seren, aderyn, cylch, allwedd, calon, hash, croes, cwpenyn dot, rhigolau bysedd, gwyntyll, hanner cylch, llinell, llaw negyddol, ongl agored, hirgrwn, coeden, pluen, llaw bositif, cwadrangl, aren, ysgol, croes heb ganol, sarff, cynllun to, sbiral, ochr-olwg to, triongl, bagl, canwyr dwbl, fforch, ac igam-ogam. O’n nhw’n ffurfio pictograffeg neu sillwyddor, gwyddor neu abjad? Dwn i fyth. Ond mae’r lluniau’n llawn nerth heb os. Ac fel gŵyr pawb, mae’r EFE wedi chwysu gwaed i greu’i hiaith ei hunan i ddrysu, rheoli a dominyddu. Efallai bydd fy ymchwil innau, er gwaetha mor bitw ac anorffenedig ydy, yn gweithredu i gryfhau calonnau a meddyliau’r gynulleidfa, a rhoi iddyn nhw daclau i wrthwynebu a thanseilio’r ymosodiadau gan y brawychwyr ieithyddol eglwysig (a dw i ddim wedi crybwyll y gwleidyddion glofoeriog yma!). O ran cyfaredd sain, bydd G.Ll. yn sôn yn helaeth am Ddisgiau Hlothu, Sgwariau Hud Thuhlo, a llefaru â thafodau maes o law. — P.M.

[**] Dw i’n teimlo bydd yn addysgol cynnwys y cofnod canlynol yma. Mae’n bennod o’r enw “Tywyll-rodio” o “Helaethu ar Hudo,” a ddechreuwyd gan yr enrhithol arbrofol Sikráks͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏͏ū Stévsū filenia yn ôl a diweddaru gan yr hudolwyr mwyaf arloesol ers hynny. — P.M.

Yr oedd y noson yn dywyll a stormus; roedd hi wir yn tresio bwrw. Y rebeliaid a ddeudai i’r Prif Frigand glew: Rhowch i ni hanes, Bencapten yr Herwyr. Ac atebai’r Pen Bandit fel yma...

O nos, O nos, O nos – Dynghedus nos! Ww, nage mi fy hun oeddwn i o’r blaen o ‘nghymharu â’r hon wyf fi yn awr. Ond eto, er nes i ddim llefaru’r eithaf ymbil, ddaru i mi chwarae efo fo; nes i adael iddo lithro trwy fy meddyliau, nes i ganiatáu iddo fy meddiannu. O, gwae fi ‘ngeni!

Mi oeddwn i wastad wedi ymbleseru’n fawr mewn ymchwilio i wybodaeth anghofiedig a gwrthodedig i ‘niddanu fy hun, plagio ‘ngelynion, a chael hyd i bethau bychain (a rhai ddim mor ddibwys ‘fyd) oeddwn i’n eu hangen a’u dymuno, fel tybiwn i, be bynnag. Wedi’r cwbl, er ‘doeddwn i ond yn berlysieuydd iselradd a naturiaethwraig hunanddysgedig, ‘doeddwn i er hynny heb gryn ddoniau cynhenid o ran hudo, swyno a rheibio. (Oedd y werin yn deud na gwrach bôn clawdd, gwraig hysbys, hen ddoethures, a meistres y sudd elfennol oeddwn i, er mwyn popeth!) Ond ers i’m henaid hoff cytûn gael ei herwgipio gan anrheithwyr y Bashr Owtlóh Hwdwmon (y cachgi ‘na o lethwr milain!), oeddwn innau tu hwnt i gysur. Fyddai’r un o ‘moddion i’n gweithio rhagor, ‘chwaith.

O ganlyniad, oeddwn i wedi mynd i fyw dan y sêr, fel cardotwraig heb na thŷ na thwlc, yn crwydro’r Byd lle bynnag y deuai ‘nhraed â mi, a lle bynnag y mynnai ‘nghalon, mewn ymdrech i geisio ‘nghariad tirionaf, a’i gael o’n ôl ryw ffordd neu’i gilydd. A bod yn onest, oeddwn i’n esgus bod yn farddes ar y slei, ac yn ennill tamaid trwy adrodd cerddi trist, aflednais a doniol i ddiddanu’r taeogion llwglyd a llawn heintiau. Yn ogystal â ‘ny, oeddwn i’n llwydo i gadw’n ddigon pell oddi wrth lengoedd sathru’r Bashr a âi o gwmpas ymhobman gan dreisio ac ysbeilio, llosgi a lladd. O, cyn amled oeddwn i wedi bod yn erfyn ar Duwdodau’r Isfyd a’r Ysbrydion Nefolaidd (yn anghyfreithlon ac yn gyfrinachol wrth gwrs) i sicrhau ‘doedd fy Tewi cu ddim yn huno mewn hedd, ond yn dal i fyw, a sgrechian, ac ysbrydoli pobl rydd i wrthsefyll lle bynnag oedd o. Ella ‘doeddwn i’m yn gweddïo’n gywir: naeth fy llais grino fel deilen farw a throi fy mhengliniau’n fadruddyn gwaedlyd ond ddeuai rhech chwannen mewn ateb fyth.

Ddaru mi, Lenre Veka, ‘lly, deithio dros y bryniau ger y pwll gol-tar yn arogli fel yr hen, hen ddyddiau, a mynd heibio i’r teulu olaf un o geirw’n pori ymhlith y mieri. Nes i gyrraedd Dwll Tin Byd i ddysgu sut mae’r môr lliw saffir ac ynddo ysgolion o forfilod yn newid efo’r nos i ddŵad yn fod byw, ei ddyfnderoedd mor borffor â gwaed neidr y llaid; ac i fod yn dyst i ddial yr celanedd anghofiedig, sydd heb amcan heblaw am gyflenwi’u nodau anllafaredig eu hun. Mi oeddwn i wedi dŵad â llyfr ymarferion dulas yn llawn swynion, sachaid o flawd, tiwb o pinnau, gwas botasau, sawl band lastig enfawr, peint o finegr, pwys o siwgr barlys, rholyn o bapur llwyd, ac asgwrn mawr gerfiwyd yn asgwrn bach, wedi’u eu begian, eu benthyca a’u caffael mewn ffyrdd eraill fan hyn fan draw. Oeddwn i’n coelio’n daer basen nhw o’r pwys mwyaf i mi weithredu’n effeithiol, er fedrwn i’m rhagweld sut bryd ‘ny. (Rhyfedd ffyrdd y wrach, fel y meddan nhw!).

Yno, ar fachlud haul, oedd yr awyr ar dân, a haid o fflamau chwaraegar yn goch, melyn, oren a phinc – fel poinsetias, dahlias, rhuddos a phetwnias – yn cosi’r cymylau uwchben y dŵr afieithus, ei liw yn debyg i werwydden neu fyrtwydd, a’r penrhyn yn pelydru’n aur fel blodau pigwrn. Yno, yn unigedd ysblennydd y gwyll wedi’i lenwi â chwerthin pellennig hyenau, ymhlith y blodau lluosflwydd pinc gwenwynig, oedd fel ‘tasai neb ar wyneb yr Wrth Druenus wedi fy ‘nabod i ‘rioed. Ac yno, ddaru i mi ddisgwyl. Naeth dydd ildio i nos. Mi oedd llen dywyll yn hongian dros wyneb y nef a chomedau’n fflangellu’r awyr wrth i’r sêr guddio’u llygaid. Naeth hi ddechrau arllwys y glaw wrth iddi nosi.

Sut des i i fod yno yn y llecyn dieithr ‘na’n neilltuol, o bob man dan Haul? Wel, o’r eiliad mi gefais i ‘ngeni, oeddwn i’n fyfyrwraig amatur logoffilia hermetig. Yn blentyn, oeddwn i wedi gobeithio gwybod; yn lodes, yn ysu am ddatblygu; yn ddynes, oeddwn i’n mynnu gweithredu. A dyna pam des i i’r lle hollol ddiarffordd hwnnw. Oeddwn i wedi ‘mherswadio o’r diwedd ildio fy ewyllys i ofynion dwysaf fy hunan dirgelaf. Ac yno, oedd y twyni gwlyb yn disgleirio dan y lleuad fel plât arian y Swynwr, a’r tonnau’n llewyrchu’n laswyrdd gan fioymoleuedd y dinofflangellogion. Mi wyddwn fod rhaid imi arddel bywyd fel y mae o mewn gwirionedd, gan wadu uniongrededd ffug, a chofleidio bodolaeth popeth anfoesol, ych-a-fi, a drwg yn ogystal a’r pethau hyfryd, er mwyn ennill y doethineb ocwlt mwyaf rhiniol ac arswydlon oeddwn i ag awydd cryf ofnadwy i’w ddarganfod.

Yno, nes i sefyll ar y traeth lle oedd Llu Marchogesau’r Stalwyni Gwinau wedi arfer dŵad i losgi’r meirw a gwasgaru’r llwch, a chrug hynafol Vendl yn ymgodi yn y cefndir, lle basai Ffefrynnau’r Llais o’r Tu Hwnt yn gollwng gwaed pur y rhai byw. Ac yno nes i gychwyn ar lwybr anwedd tuag at ynys spikni yng ngwlad tarthau. Yn unol â “Cyfrol Geiriau Anarferol” Propertius, ddaru mi osod drychau llidus di-rif i ddenu rhithiau tabŵ a medru sylwi ar bethau na welai fy llygad o gwbl fel arall. (Oeddwn i wedi rhoi’r rheibiau ar ddu a gwyn mewn ysgrifen italig yn y llyfr glas.) Nes i fy addurno fy hun â gleiniau fel llygaid dynion, lotysau tanjerîn, penglogau orangwtang, a lludw gwyfryn. Ar ôl hyn nes i offrymu yn null ymarferwr vrukhr-ía: “vathya” (potel o gwin gwaed), “vazí” (sgerbwd un o fendith y mamau), “vasha” (plât o cnawd ffres), “vuthla” (grawn a medwyd dan eclips lloerol), a “vaythna” (had dynol arllwysasid yn ddefodol); cyn galw ar i’r Rhai sy’n Aros a Gwylio ddŵad tuag at yna ac agor drws o’r anhygoel i’r posibl:

Ysbrydion yr Awyr: Consurier hwy!

Bwganod yr Wrth: Gwysier hwy!

Coblynnod y Dŵr: Galwer hwy!

Pwcaod y Tân: Enynner hwy!